Down the Great Ocean Road in South West Victoria, we discover one of the natural wonders of the Australian coastline. Nope, it’s not the 13th Apostle. It’s the legendary lobster lover Wayne Hanegraaf, who has steered boats around these ancient stones for more than 40 years in search of juicy red marine crustaceans.

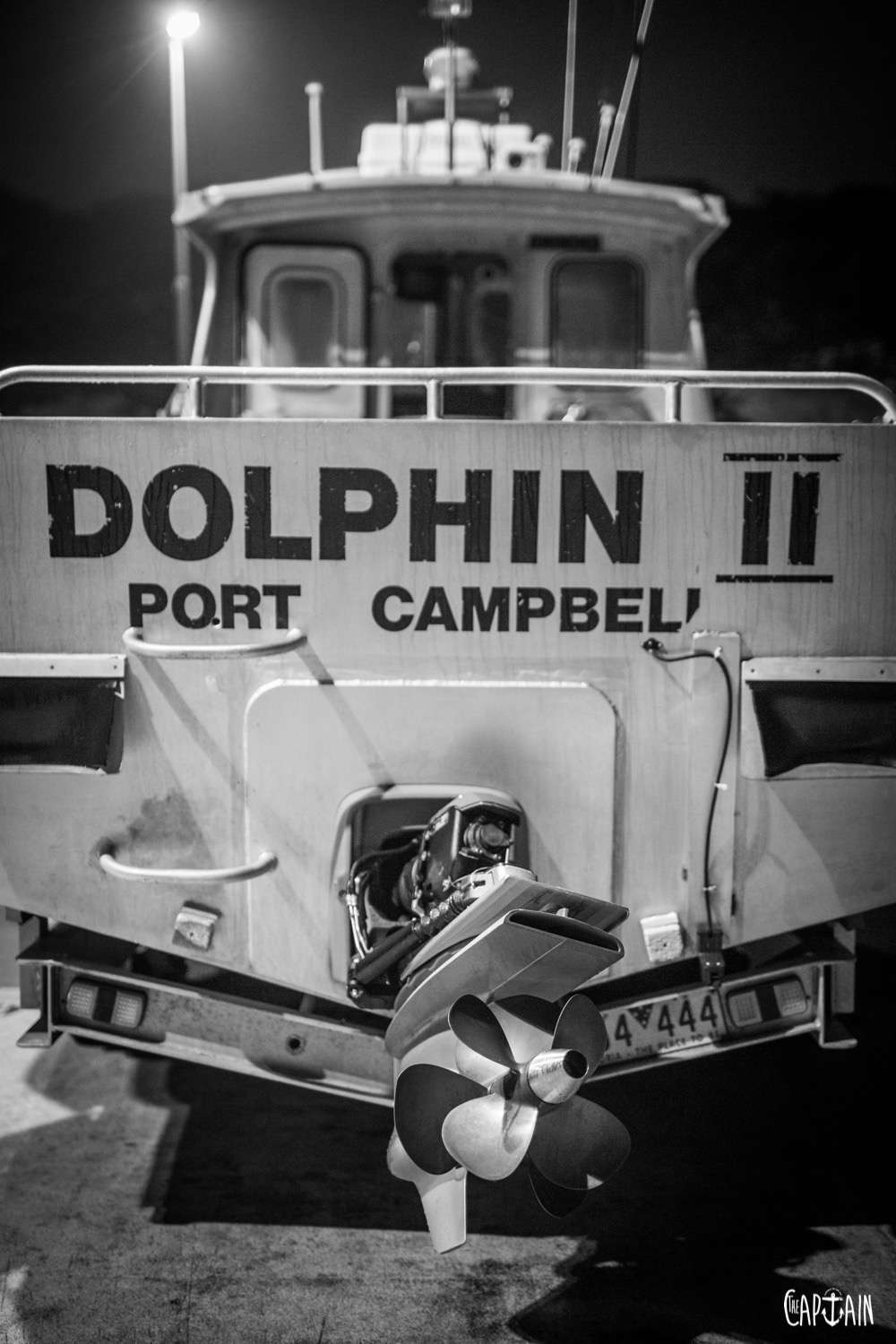

Wayne Hanegraaf never meant to build a crustacean cartel. He does it for the love of the lobster — and a life of solitude on the seas off Port Campbell. (Note: The Captain has no idea why it’s called a “port”. There’s no port to speak of, just a creaking timber wharf standing inside a bay no wider than 150m.) It’s a rough and rugged coastline — not for nothing is it known as the Shipwreck Coast. Welcome to Wayne’s world.

We catch up with Wayne at 6am at the ramp. The fog creates a Jack the Ripper haze around the wharf lamp posts and the sea laps hungrily around the rocks and pylons below. Strangely, Wayne’s dressed more like he’s going to a 1980s backyard cricket match, styling it in a well-worn blue bucket hat and brown flannelette shirt. Obviously, first impressions aren’t high on Wayne’s agenda, least of all when some bloke is poking a camera lens in his face.

Wayne clambers into his Mitsubishi Fuso truck and reverses Dolphin II, his 29ft platey, down the narrow limestone cut-in, swings into a 90-degree turn, then runs across the timber wharf that stretches into Bass Strait. Stepping out of the truck, he connects his boat to a crane via four mounting points and smoothly swings it out and down into the surging waters below. The Captain guesses Wayne has performed this impressive manoeuvre more than once. Our eyes are still adjusting to the light, straining to watch Wayne crane his 3.6 tonne boat single-handed into the Bass Strait briny with strategically placed ropes.

Motoring out of the “port”, Wayne says, “This is some of the most beautiful coastline you’ll find in Australia — big cliffs and a lot of big breakers.” He’s got it all largely to himself, with only one other commercial cray fisherman working out of Port Campbell, as well as a few keen locals brave enough to, er, brave the chill factor. “It keeps all the other pros out because not many people like working here,” Wayne chuckles.

Asked how rough it can get before he pulls the pin, Wayne reckons he can launch Dolphin II in a 15ft swell. We hang on a little tighter. The sun peers over the limestone cliffs, slowly burning the fog off the horizon.

CRUSTACEAN CARTEL

Wayne doesn’t have to fish to put food on the table. His licences are worth more than a Sydney waterfront home (maybe even two of them, adjoining), allowing him to catch seven tonnes of crayfish a year.

“I started as a kid — it was a way of life for me. It wasn’t about money in them days, that’s for sure. I just loved fishing — and still do.” The cracks on Wayne’s face reveal his years on the sea, the place he calls home. “I’m free out here. It’s rough and raw country. You’re working for yourself. There’s only you and your deckie, and as long as you get on with your deckie, life’s sweet.

CRAYFISH CARTEL

We ask Wayne how the value of his quarry has increased since the early days of paper sounders and charts. “When I started, we were getting $3.20 to $3.40 a pound,” he recalls. “Now we sell for $90 a kilo — and last winter it got up to $120 a kilo.” By The Captain’s math, that’s a 15-fold increase. “I only did it because I was wagging school and loved fishing, but it’s turned out to be not such a bad move.”

Like other salty cray fishermen we talk to, Wayne says the biggest thrill is “the chase”. “There’s not a lot of people who can go out and catch crays every day of the week and be consistent.”

He reckons the best ground to find reds is, “heavy and nasty reef, big cracks and big bommies. It’s a lot of hard work and persistence. Depending on the ground, you’ll see a ledge, allow for the tide and get as close in as you can. The pot sits there overnight and you pull it in in the morning, take out the cray and rebait the pots. Then you figure out whether to reset or move.”

This is the intuition of a master hunter-gatherer. “I fish a lot off gut instinct,” Wayne says. “I always have. I can drive a mile over ground and not like any of it. But then I’ll drive over ground and say ‘this is it’. For some reason, I keep fluking it.”

At the end of each hunt, Wayne calls Fisheries to inform them of his booty, then heads home and drops the catch in tanks. There they’ll stay until the price is right and Wayne ships them to market for live export. They can live in the tanks for months on end feasting on the bacteria created in the filtration system.

CRAY PAY DAY

Wayne’s crayfish cartel is a multimillion-dollar business run by one bloke. The combined licences on the Dolphin II alone are worth more than $6m. There’s a bit of self-restraint required — Wayne prefers not to eat them, saying he’d be chewing up $200–$300 per cray. Want a piece of crayfish cash? Here’s what you’re up for and what you can expect in return:

- Crayfish licence: $30,000–$40,000

- Pot entitlement: $1500–$2000 per pot (Wayne holds 166 pots)

- Tonnage: $750,000–$800,000 per tonne (Wayne holds almost 7tn)

- Earns: $80–$90/kg; up to $125/kg in winter

- Turnover: $500,000 per year

HARVESTER

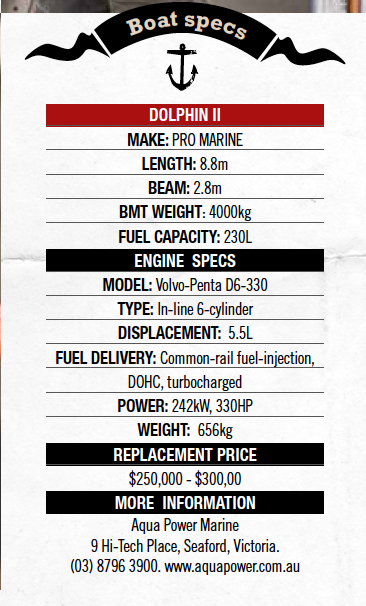

Wayne’s boat is a Pro Marine 29-footer (8.8m), built in the early ’90s. Power comes from a D6-330 Volvo-Penta. “It was always a really good sea boat with Volvo-Penta 200s, but five years ago we put the 330 diesel in it,” Wayne says. “We can steam much faster in sloppier seas — it won’t bury in the troughs and bog down to 12 knots, then motor up to 20 knots. If you want 18 knots, it’ll hover at 18 knots the whole time. Because of the electronics, you can actually hear the engine giving itself another squirt of juice.”

Driving the boat is one of the many highlights of Wayne’s world. Right now, he’s itching to drop the hammers and push it out to the mid-30s (knots), squinting into the oncoming breeze with a smile. “Coming down this channel is a nightmare for a lot of people, but we have a ball and just surf it in.” Wayne’s years of surfing have taught him how to read the swell and waves. “It’s nothing for us to surf 15ft (4.5m) waves. When I take off, I tell people to hang on. We’re running G5s on her now and we’ve actually had pots fly off the back just by gunning it.”, Wayne says.

He throws it around for fun, but says the precise handling has its practical benefits. “You feel so safe in this boat working the breakers. Reverse is incredible — you can put the thing anywhere you want to go. We had single props back in the early days and the steering was all over the place. The boat used to lay over on a chine. With the duoprops, you can leave the wheel for 10 minutes and she’ll stay straight.”

Operating in rough country takes its toll on the gear. “I used to go through the hydraulics every two years,” Wayne says. “I was literally wearing them out by swinging off the gear controls in big seas. With hydraulics, you’ve got a lot of crap to look after every year. We haven’t got any of that drama now. With the electronic gears and throttles there’s less shit to go wrong. I haven’t touched them since the day they went in the boat, more than five years ago.”

Fuel saving is also impressive with the new Volvo- Penta, which has recently clocked up 3000 hours. “We just did our whole cray season using less than 1000L of fuel, which sounds pretty bloody ridiculous,” laughs Wayne. “We used to use 55–60 gallons (210–230L) a day and today we used 15 gallons (57L). At 3000 revs, she’s doing 30 knots and we’d be using around 40L per hour. She burns that little I don’t care. All I know is my fuel bill used to be up to $15,000 a year and this year it was under $1500. I’m pretty impressed.”

Southern Volvo-Penta supplier, Aqua Power Marine, has serviced the motors since they went in. Wayne doesn’t throw praise around lightly, but gives Aqua Power a big tick. “They look after me brilliantly,” he says. “They’ve been incredible the whole time.”

Also helping keep Wayne on the water is Seacruiser boat builder Ed Richardson from Richardson Marine in Warrnambool. Ed’s crew built the tray on the back of Wayne’s Fuso and his alloy boat trailer. Wayne rates him highly, “He definitely does a good job.” It’s about the first thing Wayne’s told us that we already knew.

INTO THE GORGE

After plucking a few pots with the hauler and tipper, we head into Loch Ard Gorge for a closer inspection of the Limestone Coast.

The gorge is named after the Loch Ard, a threemasted, iron-hulled sailing clipper that sank here in May 31, 1878. Launched in 1873, the Loch Ard was not a lucky ship, twice dismasted on her maiden voyage. In 1874, she almost ran aground off Sorrento. Oh, and on another trip, her captain died. On this last, fateful voyage, all was cool until the ship turned the corner into Bass Strait, only to be smashed by stormy weather. Because of the huge waves and thick fog, skipper Captain George Gibb didn’t see the Cape Otway lighthouse. What he did see, when the fog lifted, was Mutton Bird Island — way, way closer than it should’ve been. Gibb almost managed to pull off a great escape, but the Loch Ard hit a surrounding reef, bringing down the masts, which totalled many of the lifeboats. The vessel sank in 15 minutes with only two survivors from 54 passengers and crew. The wreck was rediscovered by divers in 1967 and is now officially a “historic wreck”. (Note: The Captain has known a few of those in his time.)

Wayne says there aren’t many commercial guys that haven’t hit the rocks here at some stage. In fact, his brother lost his boat here 30 years ago. Wayne hasn’t, but reckons he’s come pretty damn close a few times.

On one occasion, his deckie thought he was thrown overboard but, he was just swimming in the water that spilled into the cockpit after a green wave swept into the boat. Fortunately, today the seas are a little kinder and we can almost touch the limestone cliff. Wayne noses into the blowhole, asking if we’d like to do a three-point turn inside the hole. The Captain’s crew do a collective stunned mullet impression before the swell picks up and Wayne backs out in quick time.

He hopes to pass on the business — and his legacy — to his son-in-law, Ben, who moonlights as deckie when he’s not working his regular gig as a chippy. We vote Ben ditches the tool belt, because he proved more than handy on deck, catching a feed of snapper and bluethroat for The Captain’s crew. (For the record, Wayne has an Ocean Access Fishery Licence allowing him to catch scale fish using long lines or traps, technically defined as pots under his crayfish licence.)

Wayne reckons he’d like to fish for another two to three years before hanging up his pots. “That’s a long time out at sea. Not too many people do more than 40 years in this place.” He’s contemplating a bigger boat, but he’ll never part with his trusty Dolphin II because this boat delivers lobsters daily — both the spiny kind and the $20 banknote kind.

Recent Comments