Time to rip and strip Nub Tub, the Captain’s Haines Hunter 445F back to bare bones before building her back up to survey class, courtesy of Erick Hyland from Whitepointer glass boats in Cann River, Victoria. Erick shares his version of events…

The moment The Captain’s Haines Hunter 445F rolled into Eden, I knew they were in deep shit. They claimed it had a new floor and gel coat, but I reckoned if it was riding on its original stringers they’d be rooted, along with the transom. They weren’t built to last 40 years. I know this because I was taught in the Haines Hunter factory. Don’t get me wrong, they just built them to the standard of the day and nobody expected them to be sought-after classics 30 or 40 years later.

All the same, a well-rebuilt boat will last a lifetime. When it comes to materials and construction below the floor, there are plenty of options, many of which I’ve tried. These days, I only build a dozen boats a year, so I’ve got to get it right. If I screwed up just one boat, abalone divers Australia-wide would let me know about it – they make up 90 per cent of my customers. They’re known for being particularly rough on their boats, loading them up day after day, operating in huge seas and carrying huge horsepower. They work them to death. I reckon most abalone divers could fuck up an anvil with a cork hammer. So I think The Captain’s project boat is in pretty good hands. Anyway, I’ve used almost every boat building material (alloy aside) and this is what I’ve learned.

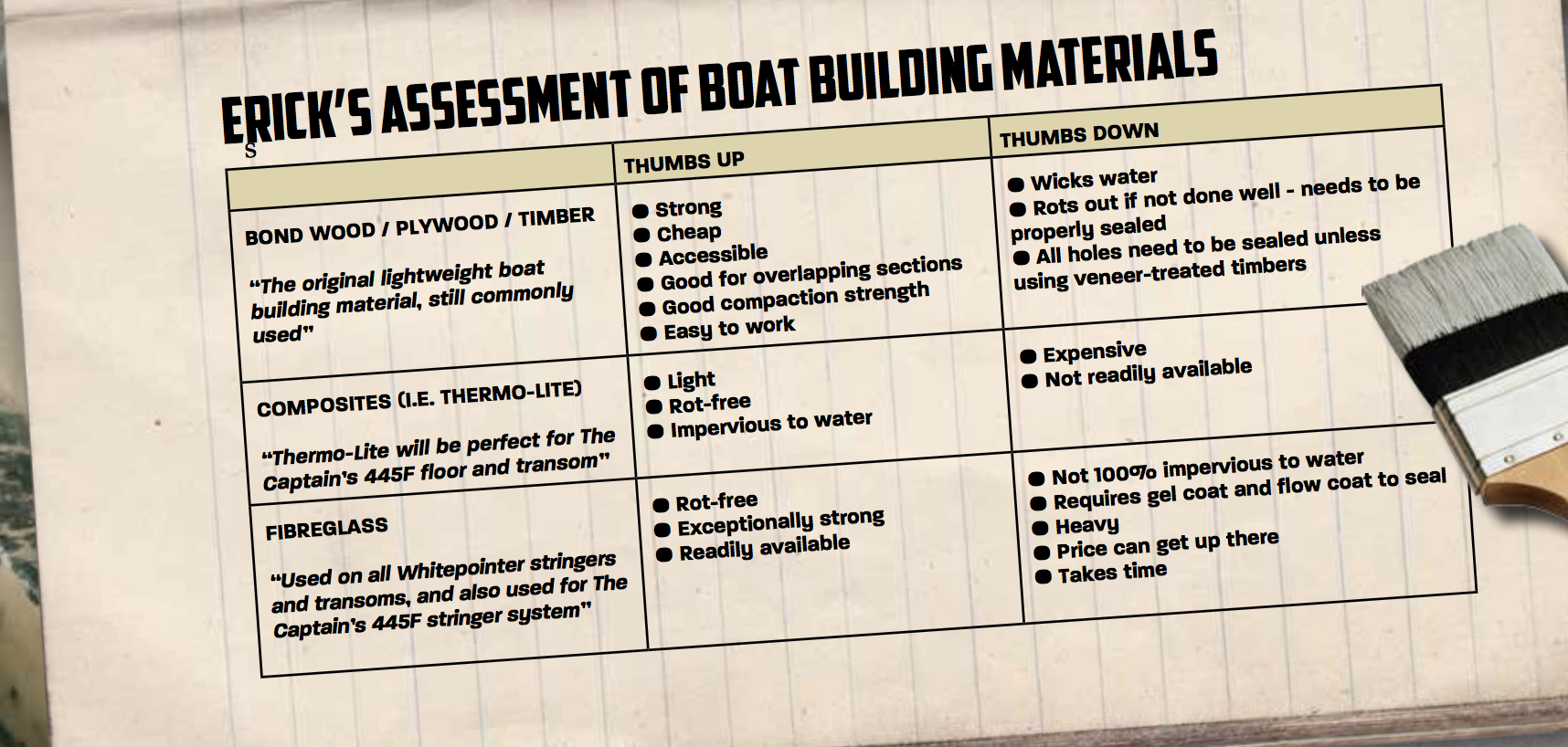

BUILDING MATERIALS

There are three main materials to consider when rebuilding a boat floor and stringers. Before composite and fibreglass, bondwood was the most commonly used material inside and outside the boat. I still use timber for the floor because I reckon it holds a screw better than the composite materials, but to be honest, plywood is only really good for building dog kennels. Many builders still use timber for stringers. They say it reduces noise and vibration and if treated right will never rot out. That may be true, but there’s a bigger reason: time and cost. I switched to ‘glass 15 years ago. There’s no worry about noise and vibration in a Whitepointer 263 hull that tips the scales at almost two tonne when it’s dry.

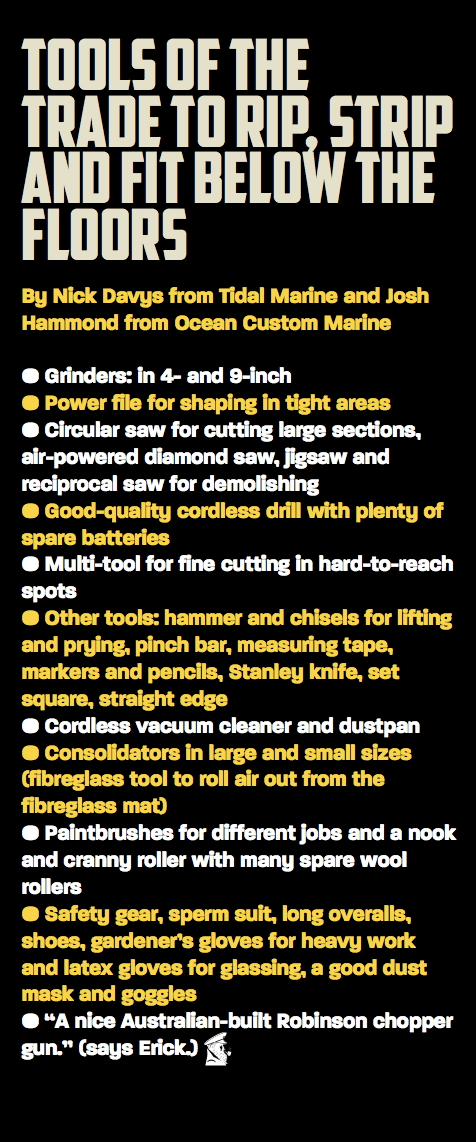

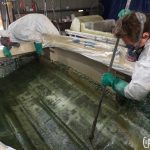

By the time the project boat arrived at the Whitepointer factory in Cann River, it had been well and truly scraped out. In fact, I think I saw daylight in a couple of spots.

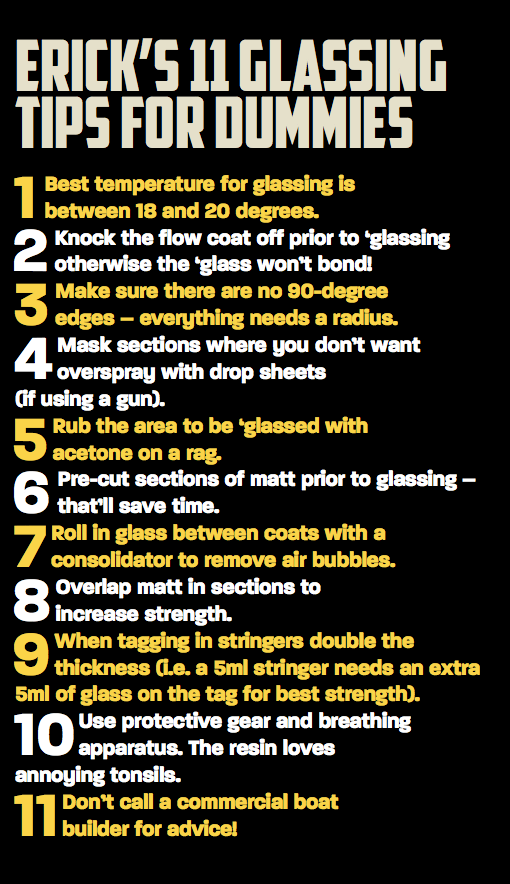

First we masked areas we didn’t want ‘glass on then wiped with acetone before hitting with a gun pass of 600g. Then we laid two layers of 800g gram rovings overlapping at the keel, then another layer of 800g roving over the top, dusted with a light layer of chop strand in between. For a bulletproof finish, we hit it with a final gun pass of 600g chop over the top. In some areas, it’s now double the thickness of the original glasswork.

THE STRINGERS

The stringers for The Captain’s project boat are based on the ones I use for the 5m Whitepointer Super Hornet and big 263 model. They’re a C-shape, forming a full box section when ‘glassed in. They’re made up of five layers of ‘glass using 800 roving and 600 chop. Once shaped to fit snugly into the 445, we glass them in around the outside edge with chop strand, two layers of roving and chop again over that, applied with the roller. Essentially, it doubles the thickness of the sidewall of the stringer. The commercial survey assessors like it that way. On my bigger boat (the 263), the stringers are also glassed on the inside section of the join, just for extra strength. The stringer box sections can then be foam-filled or left open to drain. On the project boat they’ll be fully enclosed and watertight buoyancy chambers, but with a bung for draining.

Recent Comments