If John Haines Sr is the father of Australian monohulls then Bruce Harris surely owns the title for Australian Cats. What’s more, Bruce doesn’t owe anything to the Yank designers for his achievements — he did it all with good ol’ Aussie ingenuity, designing and building what would become Australia’s most legendary cat brand.

In a sprawling, dusty yard in a Gold Coast suburb, the perfume of freshly cut hardwood, fibreglass and, er, honey wafts on the breeze. This is where The Captain finds Bruce Harris, father of the Shark Cat. He’s weaving his motorised scooter between beehives, past an old 18ft clinker hull and into a shed that’s home to a new 23ft prototype cat. It’s just had a spot of glass work finished and The Captain happily breathes in the familiar fragrance of Australian boat building. (Note: The Captain always inhales.)

We manage to grab the handbrake on Bruce’s motorised scooter and put him into neutral just long enough to get him to tell his tale. His wife, Daphne, serves us hot tea, salad sandwiches cut neatly into triangles and a generous plate of Arnott’s Butternut Snaps — in between ferrying photo albums and filing cases. As Bruce slowly winds into the story, The Captain sensibly suggests, “We might need a few more cuppas to see us through.”

CAT OUT OF THE BAG — WHERE IT ALL BEGAN

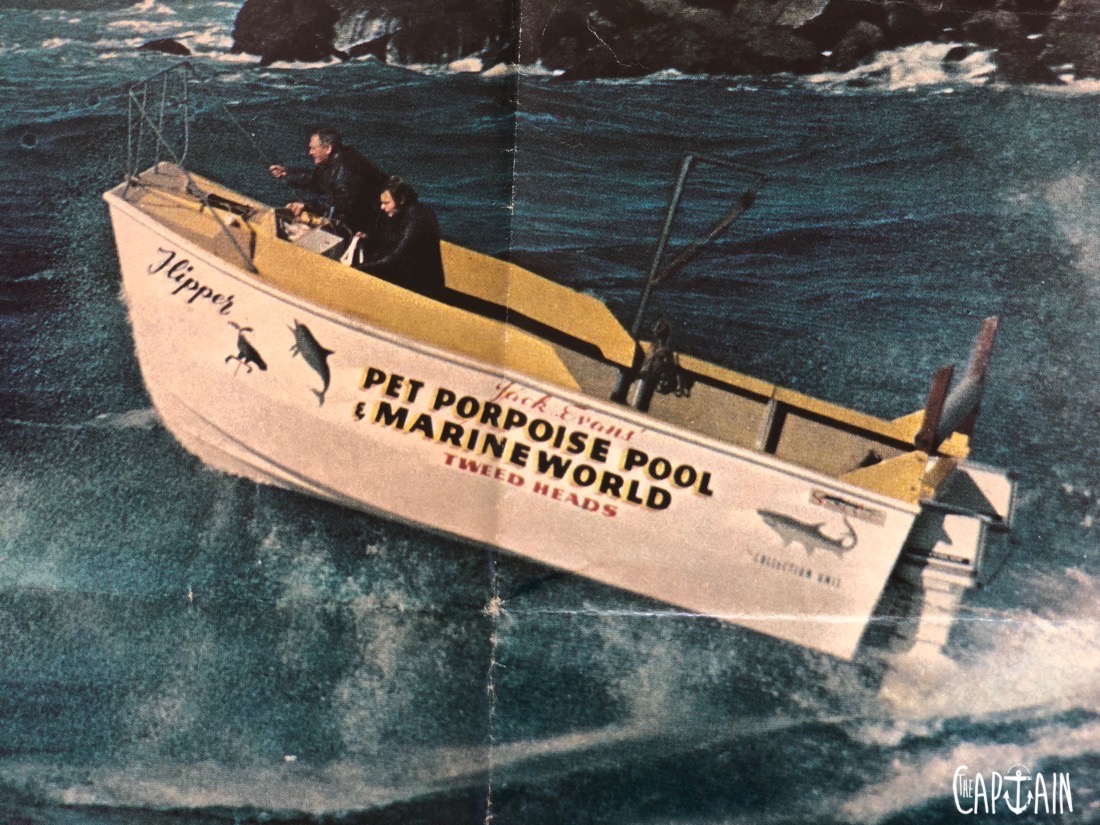

In 1958, Sir Robert Menzies was prime minister and the FC Holden was Australia’s best-selling car. Bruce was a prawn fisherman in his early twenties, fishing out of Stockton Beach, just north of Newcastle on the New South Wales coast. One morning in May, he decided he’d had enough. It was snowing at Barrington Tops (100km away) and so cold he had to pluck his prawns underwater so his fingers wouldn’t freeze. So, at 4am the next day, his timber trawler loaded to the gunwales, he steamed out past Nobbys Head and headed north. Navigating old-school style, guided by paper charts and a compass, he didn’t stop until he got to Bundaberg in Queensland. Several days later, he was trawling for banana prawns. Fast-forward a couple of years to 1962, and Bruce — with his dad, Ollie — scored the contract to shark net the Sunshine Coast and Gold Coast, earning him the nickname “Sharkie”.

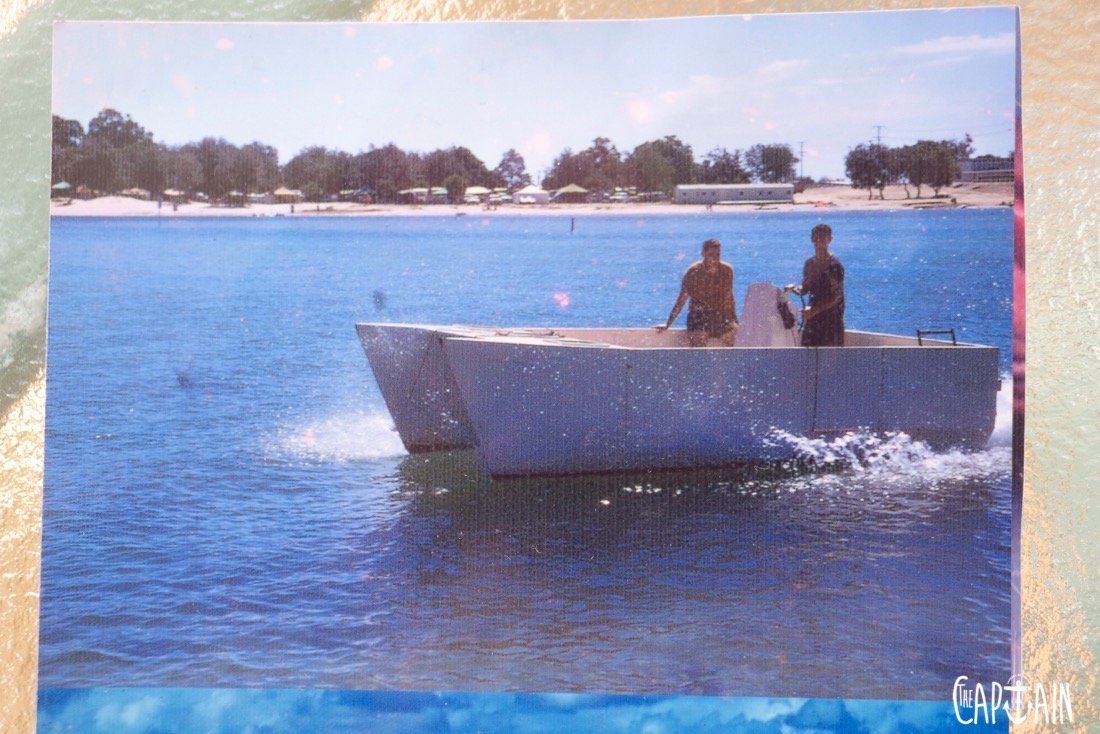

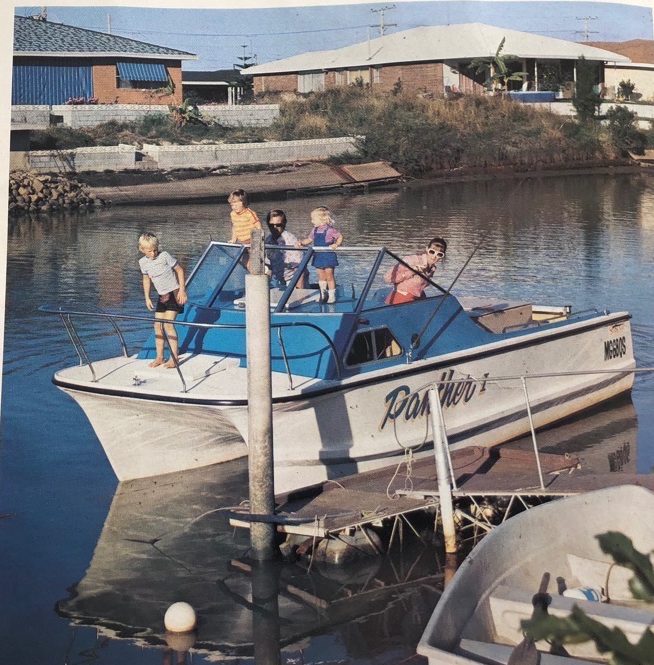

One Xmas Bruce decided to build his father-in-law, Fred, a boat. How hard could it be? After all, he used to draw and build boats in the sand at the beach. Bruce picks up the story. “I used to watch the Quickcat sailing catamarans going in and out of the surf at Kirra, on the Gold Coast and reckoned I could build two hulls and put a plywood box on top. It turned out pretty good. Fred rejected it at first, but after he put his little 5HP Johnson outboard on it and went out in the water he came round. My daughter saw me building it under the house and said, ‘Dad, it looks like a tippy willy’. So we called it the Tippy Willy.”

LOOK WHAT THE CAT DRAGGED IN — BRUCE PUTS TIPPY WILLY TO WORK

“One day my trawler broke down,” Bruce continues. “A mate said, ‘I’ve got a 20HP outboard here, how about we put it on the Tippy Willy?’ I wasn’t sure, as I’d never even been in a speedboat — and there was no breakwater back then just a sandbar. Anyway, we put it on and realised how much easier it was to pull the shark nets in. It used to take me two and a half hours to steam out at eight knots from Coolangatta to the Gold Coast, but I could do it in 40 minutes in the Tippy Willy.”

Bruce saw the potential in the new tub and put some of his design instincts to work. “I realised how good it was, but it didn’t have a proper front on it. I also realised it wasn’t strong enough — it was only built out of quarter-inch marine ply — so I decided to build a glass boat.” There was one small problem — Bruce had never built a boat from glass before. That didn’t stop him. “I walked into a boat-building factory down the coast and had a look around. The owner wasn’t too happy, told me if I didn’t get out he was going to boot me out, but I found out how it was done.

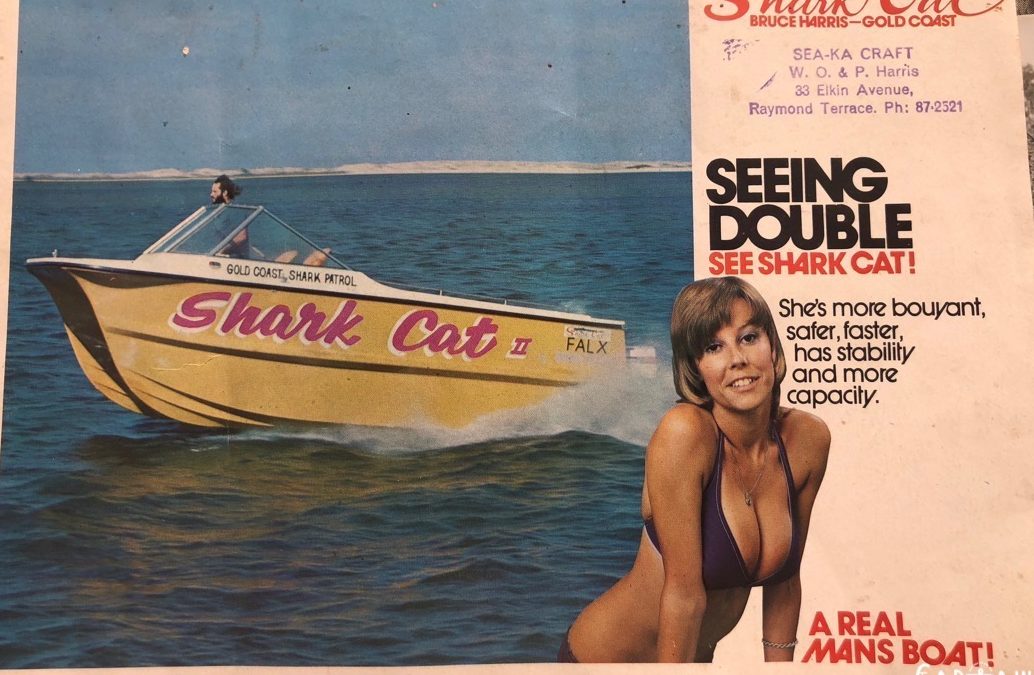

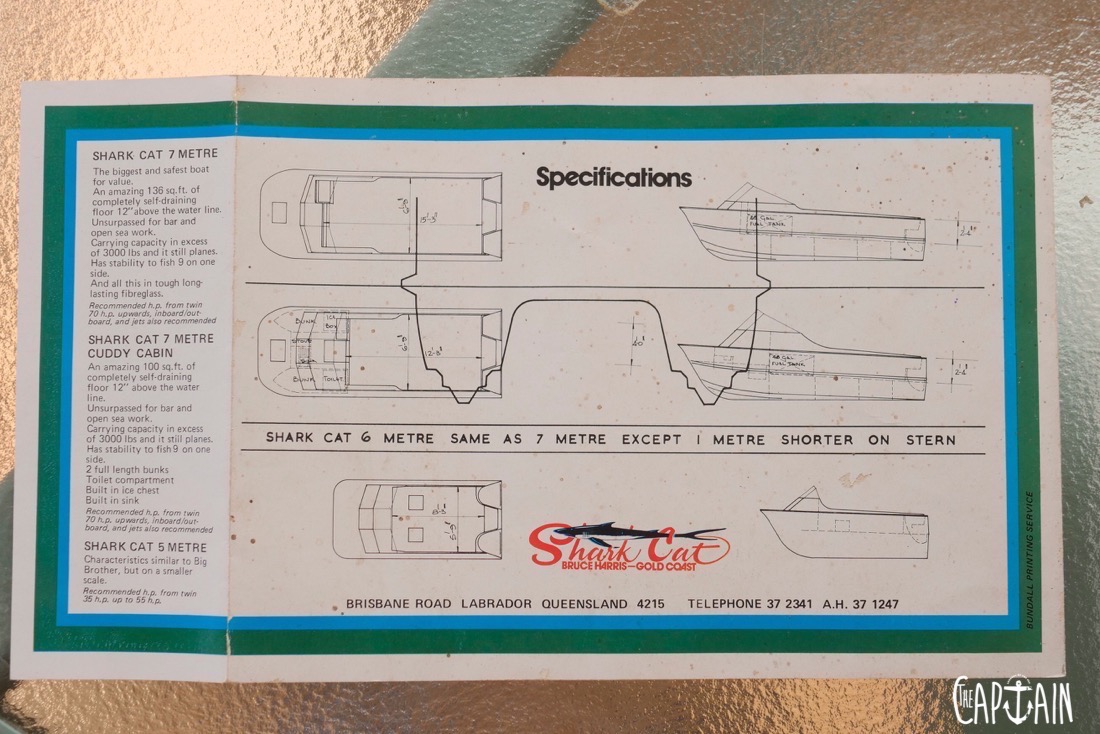

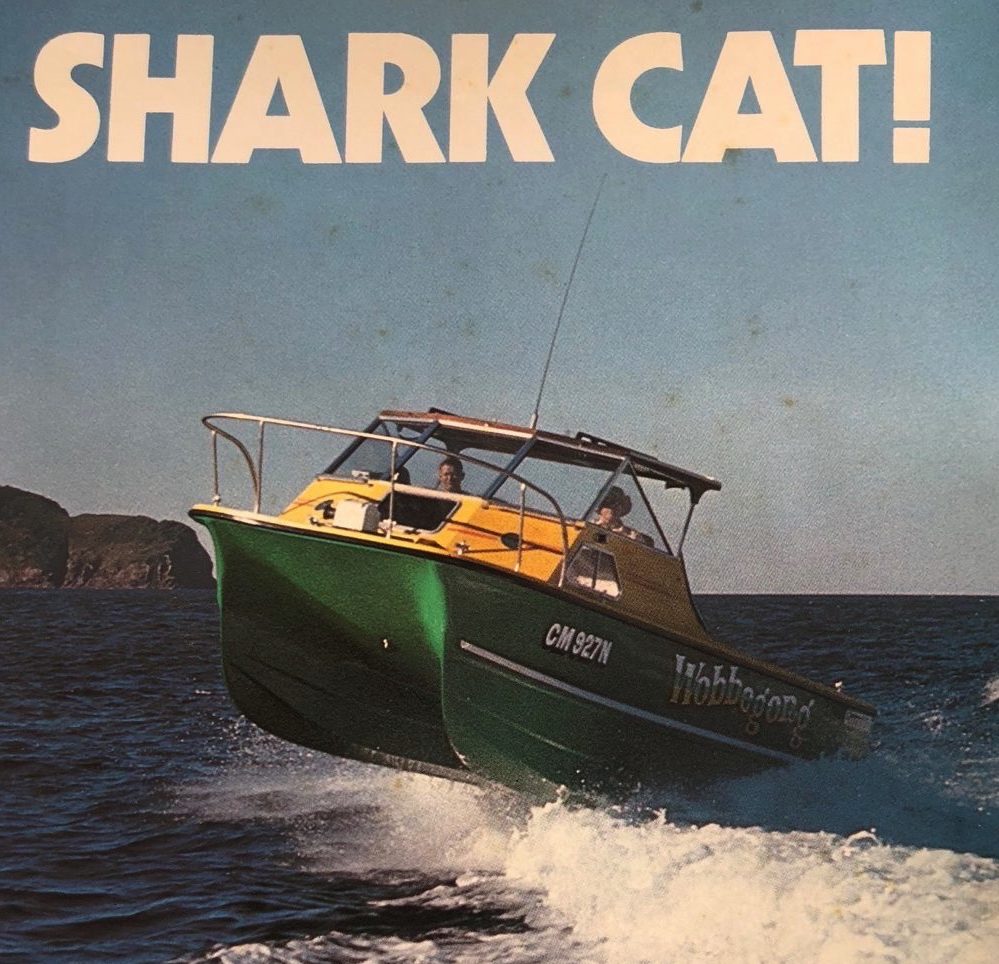

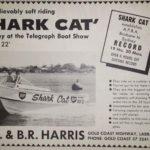

So then I made a mould out of Masonite under my house and built my first Shark Cat. Everyone used to say, ‘Here comes Sharkie’s cat’, so I decided that’s what I’d call it.” Bruce says it was pretty slow going at first on the boat-building front. “It wasn’t right, it was a bit wet. I finished up cutting the mould about six times to get the right shape before I built one I was happy with. I had no intention of going into it (production), but Queensland Department of Harbours and Marine wanted a boat for survey work in the surf. I told them I’d lend them the mould, but they wanted me to build it. So we got into it and it just took off.” And so the Shark Cat business was born. The boat attracted interest from the boating media after respected boat tester Peter Webster took a ride and gave it a glowing review. Then the business really took off.

“Air Sea Rescue, Fisheries, Police and Coast Guard got interested — I was the first training leader for the Queensland Coast Guard. Then the abalone blokes and professional fisherman started using them — I think half the abalone boats are still in the industry.” At the peak of production, Bruce had 42 people working for him, building two boats a week, with a waiting time of nine months. He sold a few to Americans. “They were all grey,” Bruce recalls. “I was a bit suspicious — I think they were going into the drug trade.”

CAT AMONG THE PIGEONS — BRUCE DOES IT HIS WAY

“I wasn’t the first to invent the cat,” Bruce says. “But probably the first to make it perform like it did. Earlier catamarans never had enough clearance above the water and pounded badly.” The main deck on a Shark Cat sits about a foot above the waterline, trapping an eight-inch deep pocket in the tunnel. When the pocket is filled with air and water (vapour) it creates a cushioning effect. The boffins tell us air on its own can’t be compressed in this environment — and water on its own is too hard to compress, but mix the two and you’re floating like Bob Marley at the One Love Peace Concert. The hull lands on tapered sections nine inches wide, opening to 18 inches when fully submerged.

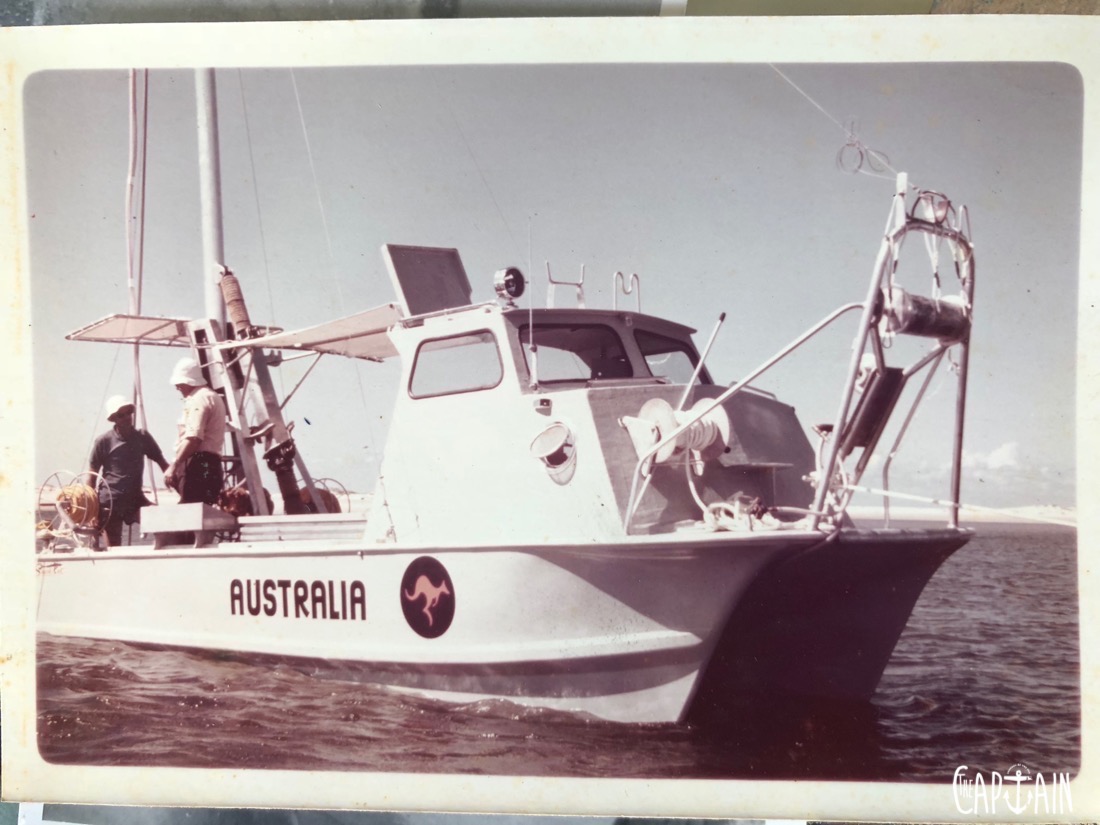

The Shark Cat occupies about half the water surface area as a monohull. This displacement helps with the low planing speeds and efficiency cats are renowned for. Shark Cats proved a big hit with the professional fishing industry. They could travel at high speed in open seas, carrying 3000lb of payload and up to 1000L of fuel. They also offered twin motors for safety and self draining decks with huge scuppers should they cop a big green wave.

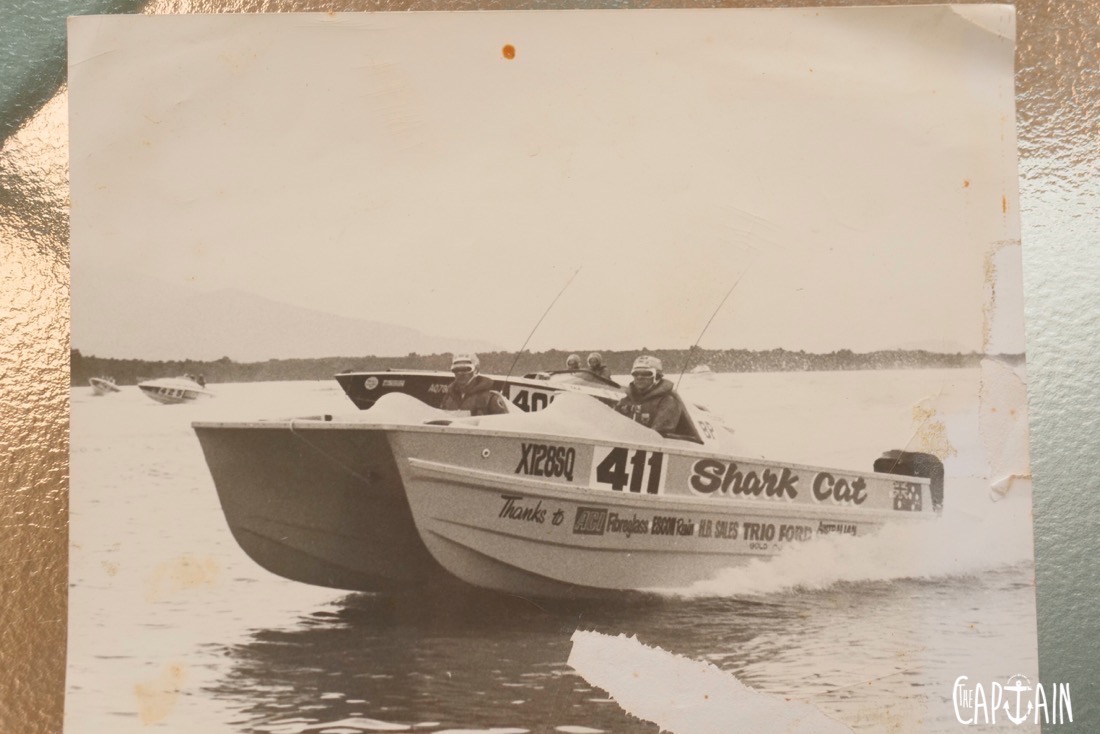

Bruce credits his racing days for design refinements that included wider planks, extra chines and flared bows. Effectively, he was his own on-water R&D department. “The beauty about racing was I could work out how to make them go faster,” Bruce says, cracking a fat grin as he recalls his go-fast days. “The monohulls with planks were getting up and going very, very fast, so I put a big plank below my boat. It was a lot faster, but it was a lot harder running. I could get away with it with my 18ft boat, but on the 20ft it wasn’t real good.

So I took the plank off and made it a round bottom shape, using a length of four-inch galvanised pipe. I put more little chines up the front, which made so much difference, and I flared the bow —for the simple reason that when I went into a wave the flare would throw the water clear and give a lot more lift. None of the cat builders today have got that flare in the front compared to what I had back then.”

In the ’70s, Bruce knocked out three or four 18ft models for every big boat he built. Inspired by Cruise Craft, he put a clinker configuration into the sidewalls of the 18-footer, making the boats lighter and stronger. He also built a split mould for the 20/23-footer. This was designed to increase the waterline beam a couple of inches without blowing out the beam at the gunwales. The final hulls were joined and capped with rubber or aluminium. The 20-footers were pulled out of the same mould as the 23ft after they were blocked off.

CAT ON A HOT, TIN ROOF — GETTING THE BEST OUT OF THE CAT

We’re onto our second plate of Butternut Snaps by now, and Bruce can practically smell the two-stroke, so we ask him to describe the ride in one of his boats. “To hop into a Shark Cat, particularly if you haven’t been in one before, it’s the most wonderful feeling, Bruce says. “To feel the response of the big motors on the back, you just give it to it and the boat gets straight up on the plane and you’re floating on top of the water. There’s no hitting hard — the air gets underneath, especially running into the wind. We’d get on top of the bar with the waves breaking under us, and just gun it off. She’d fly through the air — always stern-first — and then you’d be on top of the next wave that’d already cracked. I loved being in the boat.”

“What about sharp turns around the buoys, Bruce?” The Captain asks with a smug grin (for those who don’t know, hard turns aren’t a big cat’s strong point). Bruce draws a patient breath. “You’ve got to get used to turning with a cat. They lay out on turns whereas a normal (monohull) boat lays in. If you haven’t been in one when it starts to lay out, yaaaaaww!”

Bruce is now leaning a fair way to the right in his chair, a wry smile on his face. “Once you’re used to it, no worries. The secret to driving a Shark Cat is the trim. Say the seas are coming on your port side — you have to trim the portside motor up and trim your starboard motor down. You’ve got to get used to the idea that if you lift your portside engine you’ll be lifting your starboard bow up — and vice versa. The best way to set up a Shark Cat is to have it heavier at the back than the front. They’re two narrow fronts and perform best by lifting out of the water and coming back into it slowly. The air under the hull helps this action.”

CAT’S WHISKERS — BRUCE’S FAVOURITE

“What’s your favourite Shark Cat, Bruce?” queries The Captain — a question Bruce is often asked. “I always liked the 20-footer with the round bottom and double chine,” Bruce says. “I came first in the Sydney to Newcastle in ‘72, racing in the 200 cubic inch class against John Haines in his needle-nose Haines Hunter Formula. We were up there on a couple of stools, laughing — averaging about 50mph with the twin 100HP Mercurys. It could do 62mph in calm water.” Bruce confesses to having had some non-regulation ballast on board.

“I’d done the shark run from Burleigh Heads to Tweed before we left. When I got to Sydney there were still shark fins and part of a shark net on board. The scrutineer was horrified by the smell!” Only two boats beat him into Newcastle, both 36-footers. Bruce knew the area well from his prawning days, running close to the shore in the rough conditions with the strong sou’westerly blowing.

CUT CAT — BRUCE TAKES THE WORLD TITLE

Bruce eventually built a dedicated racing boat — the 28ft Sharkie’s Cat. “It couldn’t be beaten,” he says. “I had four 175HP motors on it and we could do 85–90mph. I won the world title in 1980, just ran away with it. I really liked that boat. We built a 32ft cat with Tony Low. He put four 200HP motors on it and we won the Pacific race from Cairns to Southport.”

Despite Bruce’s racing success, there’s no air of arrogance. In fact, there’s not a trophy in sight. They’d probably just take up space he needs for his homemade honey operation. Nevertheless, we put the question: “Where’s the trophy cabinet, Bruce?” “I’m not a bloke who puts his trophies up, I just considered myself lucky to be racing,” says the humble cat whisperer. “I won the world title and they gave me a goddess or something. I brought it home, unscrewed the head and threw it in the bin, just kept the wooden end. I’m a Christian and I wouldn’t have that goddess in my house.”

SCAREDY CATS — FLIPPING OUT

Cats do have their detractors, some of them ignorant moderators of monohull fan pages, wilfully blind to the legacy cats have earned in the Australian and world racing scenes — as well as in service with the emergency services and in commercial industries. Bruce acknowledges the stigma, noting some cats have perpetuated the myth.

“The biggest mistake most people make is that they don’t make them (cats) full enough in the front, and they don’t make the chines come up,” says Bruce. “Going into a sea, you’ve got to have a boat that wants to lift, but if they’re too sharp, all they want to do is go into the wave. The Shark Cat has a ski in the front and two to three-inch chines either side, and as soon as it goes into the wave it wants to lift.”

When pressed on models he thinks tarnish the cat name, Bruce sighs, but won’t dob in any brands. “A bloke in the Air Sea Rescue asked me if I would teach him how to drive another cat that was being built in NSW and I said I would. Anyway, in calm waters with a wave going past, I went to do a turn and it scared the heck out of me. The bow just went into the wave and kept going down. There was nothing to get it up, just a straight vee, no chines. I rang the bloke that built them and told him, ‘You’re going to give cats a bad name’. He went crook at me, said I didn’t know what I was talking about, but now he’s gone out of business. I’d say he didn’t go out in his own boat — just wanted them to look pretty.”

DEAD CAT BOUNCE — BRUCE’S KEEPS BUILDING

In his heyday, Bruce would be up at 4am. “I’d change the baby’s nappy, give her to Daphne and wouldn’t see her until 7 o’clock that night. She thinks I’m a bit of a workaholic. That’s why I sold the Shark Cat business — I promised Daphne a trip to Europe.” Bruce never numbered his boats, but estimates there must be around 1000 cats with his fingerprints on them. That figure doesn’t include the Shark Cat-branded cats that were built after Bruce sold — including some models branded Noosa Cat.

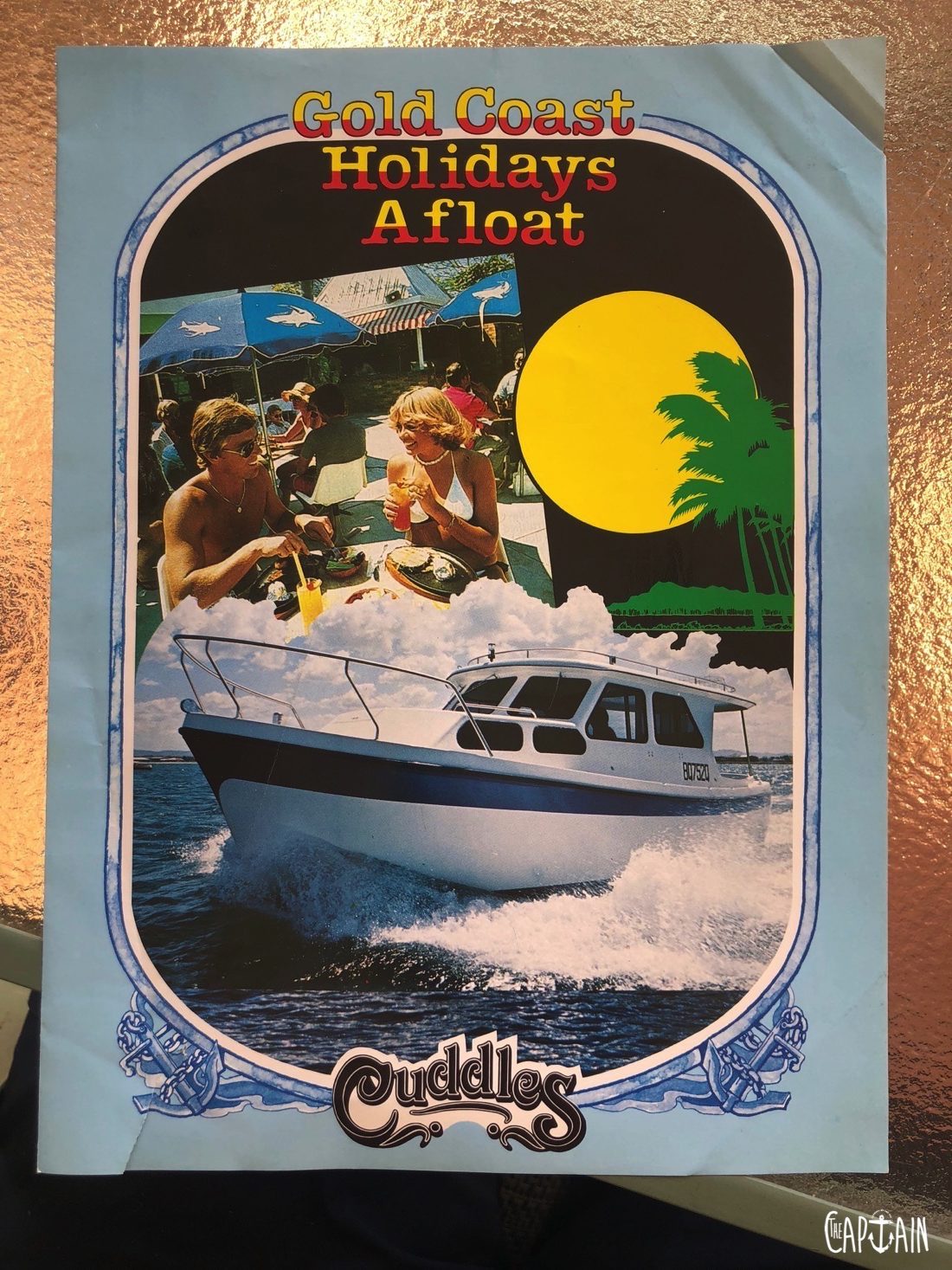

We ask Bruce how he feels when he sees a Noosa Cat. “It makes me feel very good to see them. They’re a bit different to what I did. Some of the bottoms of the 18 are still the same, but the tops are much more refined and look very nice.” After the sale, Bruce started building a 9m round-bilged monohull called a Cuddles Cruiser. “That turned out to be a very good business. I sold a lot of them — mainly 30- and 35-footers. Then I sold up that business and thought I’d retire. But I was getting bored, so I built myself a marina at Coomera (later to become The Boat Works).

Bruce also started a houseboat business, selling and hiring them out of his Coomera base. He fitted them with hydraulic Yamaha motors on the roof so they wouldn’t get wet. And Bruce kept on building boats, including a 60ft cat with a 26ft beam in which he took the family cruising around the Whitsundays for four months.

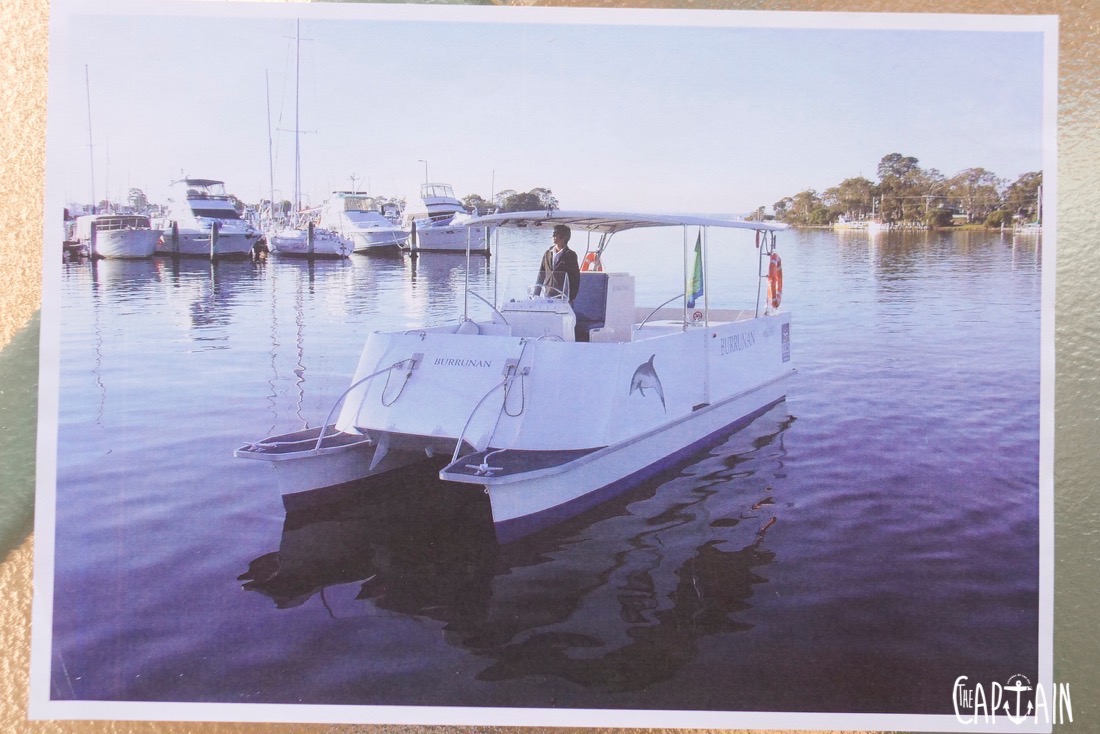

One 30ft model, fitted with twin Volvo diesel stern-drives, was rented to a gas corporation that used it to survey underwater pipes. “It was skippered by Grant Shorland from Mallacoota (see issue #10 for Grant’s story),” Bruce says. “They must have paid him a lot because he was one of the top abalone divers in Australia.”

Bruce admits that he finds it hard to stop building boats. “I’m only 80 years of age — all I know is boats. I haven’t had another job in my life. Even when I retired, I built boats, including party pontoons that are still operating in Lakes Entrance.” They feature a forward folding entry that Bruce designed for easy access. He still has the mould and has plans to sell it, lamenting that he can’t build it himself.

Mobility is an issue for Bruce these days, after a car accident that partially crushed his legs.

The love of boats has never left him. He still draws boats, mainly fishing boats and trawlers. “These old wooden boats, they talk to me.” Now beehives take up most of his time, producing Bruce’s delicious Harris Honey. “I make creamed honey and ginger creamed honey. People love it so much and it gives me something to do. I give a lot of it away.” Having persuaded Bruce to part with a couple of jars for testing purposes, The Captain can verify it’s a good brew, especially the creamed honey.

MORE THAN ONE WAY TO SKIN A CAT — THE HARRIS FAMILY LEGACY

Bruce’s son, Ian, designed his own cat, which now sits in Bruce’s shed. It features a stepped racing bottom and the top decks of an old Markham Whaler. “It’s called New Generation Shark Cat. “You might see them on the market one day”, Bruce says. Ian certainly has the genes — and the chops — to do it.

He currently builds and repairs racing boats for Bill Barry Cotter at Maritimo. He’s not ready to throw in the towel just yet. Bruce’s brother also joined the boat-building scene for a while. His rig didn’t have quite the same prestige or seaworthiness as Bruce’s boats — being made out of beer cans — although the Shark Cat resemblance is uncanny. But he continued the Harris winning ways, taking out a beer can regatta in Darwin.

Bruce Harris, The Captain salutes you. In fact, we just made you our inaugural Immortal Captain.

Recent Comments