With your best interests at heart, this hit list of “bad shit to watch out for on the water and how to deal with it if it happens” (compiled by The Captain’s favourite seagoing sawbones, who has more letters after his name than the alphabet) should keep you safe and sound while you’re on the hunt.

Australia has some of the most spectacular and varied oceans, estuaries and rivers in the world. It’s the playground for The Captain, his crew and followers. Non-fishos feel sorry for the fish, but it’s not such a one-sided game. There are just as many elements out there hunting us. Epic forces such as the sun, wind, water and cold temperatures; and marine creatures with teeth, barbs, stingers and toxins they use for defence – or that sometimes just hang in their flesh. There are bacteria, viruses and parasites chomping at the bit to attach themselves to a juicy host.

If that doesn’t kill you, then maybe one of your drunk and/or weary crew will take you out by making a bad call at sea. After a bout of cellulitis in Alaska (read about it on page 120) The Captain ordered me to put together a hit list of potential fishing killers to provide a pre-emptive safety shot across the bow for watermen in their potential time of need.

This misadventure is a tragedy easily avoided. Unseaworthy vessels, faulty or nonexistent safety equipment, solo divers and a “she’ll be right, mate” attitude towards approaching storms all lead to drowning deaths. Every time you get in a boat, it’s important to ask and check safety gear and your dive buddies’ approach to “one up, one down”. I’ve been in some horrendously ill-equipped boats, had a few near-misses and the grey hairs remind me how easy it can be to walk the proverbial plank on board a boat with a reckless captain. EPIRB, radio, life jackets, flares and a dive buddy who won’t swim off like Dory in Finding Nemo are all lifesavers.

To treat a drowned mate, you need to perform Basic Life Support (BLS). No-one has ever regretted doing this simple course, even young kids have been known to resuscitate their parents with BLS skills. Drunks fall overboard, kids slip into rough seas, divers push their limits and black out, boats sink. You’ll earn a year of free rounds at the marina tavern if you prepare for these inevitabilities. Do a basic life-support course and keep your family and mates away from Davy Jones – that bastards’ locker is full enough.

Lacerations and grazes seem like a minor concern when you’re battling barrels or pulling crayfish from honey holes. But those cuts and scratches create an entry point into the largest organ of the body – that’s the skin for those who missed biology class, not your mainmast! It’s a “free entry” sign to millions of bacteria and parasites itching to dive, balls-deep, into your moist skin, then into your fat and blood vessels until they’re surfing the red currents through your body.

An innocuous cut exposed to salt, brackish or fresh water needs your attention. I’ve seen healthy, fit young blokes laid low in a hospital bed for days waiting for heavy-hitting antibiotics and their own immune systems to fend off these stowaways and recover. If you’re a little older, less robust and have a dicky heart, lungs or medical conditions like diabetes or liver issues, then meeting some of these organisms can lead to limb loss or death.

The first step is to clean your wound well with an antiseptic scrub and keep it dry and clean. (Warning: this may well end your fishing for the day.) If you develop heat, redness, oozing pus, tracking pain, swelling, lymph node enlargement, pain or fevers, then you’ll need more than your missus and a few beers. Go to your GP and get checked out. Antibiotic choice is very important in these infections, so don’t just grab the half-finished pack from your bathroom, as you’re likely to cause more harm. If you haven’t had a tetanus booster in a while, you’ll probably need one. A member of The Captain’s crew recently left a little cut unattended while overseas and developed a cracking case of blood poisoning. If only he’d invited a capable sawbones on the trip (like me) he may have been able to continue fishing the deep blue of the Alaskan coast instead of waiting for a sponge bath from a hairy, heavyset male nurse.

CIGUATERA: HORRIFIC HITCHHIKER

The legend surrounding ciguatera poisoning and how to test for it rivals that of Blackbeard’s infamy. Ciguatoxin is produced by dinoflagellates, aquatic organisms ingested by fish. Varying levels of the toxin are stored in fish flesh and cases of poisoning have been reported from barracuda, sea bass, chinaman (displayed above), groper, coral trout, mackerel, tuna, red bass, emperor, cod and moray eels, which have the highest toxin load of any fish. Fishermen from the Sunshine Coast north have a healthy respect for the toxin as they usually know someone with a horror story. Any hardy soul who spears or pulls one out of its hole and dispatches, fillets and eats it is braver than me.

Local knowledge around which fish in your area are risky is vital, as suspect species and fish size can change with location. Even seasonal change alters case identification and some reefs can be loaded while others nearby can remain unaffected.

If you’re poisoned, expect gut symptoms after 12 hours such as vomiting, diarrhoea and cramps; and within 24 hours, neurological symptoms including numbness, itching, imbalance and cold allodynia (pain from cold stimulus such as water). Oddly, some victims report a switching of the hot/cold sensation – so a cold beer might feel hot and a hot coffee cold. This switching of perceived sensations has led to extreme pain at ejaculation – try explaining that one to Mrs Blackbeard!

Treatment involves rehydration and simple pain relief. The symptoms should fade with time, but any future ingestion of cigutoxin will lead to recurrence and worsening of symptoms. Blackbeard supposedly once shot a man dead without provocation. When asked why, he said, “If I don’t kill a man every now and then, they forget who I am”. No-one forgets ciguatera poisoning, so I’m labelling this one a true bastard of an illness.

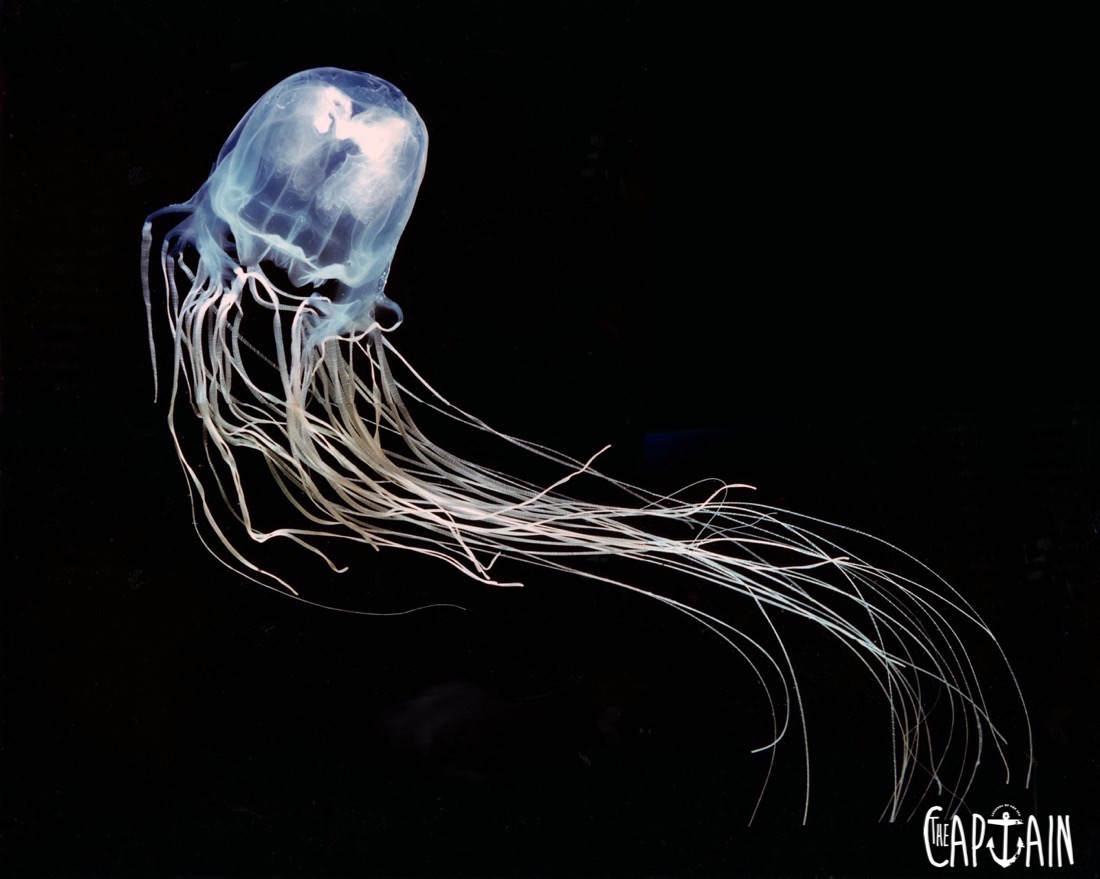

IRUKANDJI: THE MINI MURDERER

Tiny and rarely seen with the naked eye, just the name irukandji is enough to bring a tear to the eye of the most seasoned seamen in the north. The initial sting is such a trivial brush that you might even get your crayfish bundle back to the boat before you’re crippled with pain. Backache, headache, gut and chest pains, vomiting and sweating can all leave your average feisty fisho rolling on the deck screaming for hard liquor. Don’t uncork the rum just yet. That fast heart rate and rising blood pressure caused by the huge adrenaline release can lead to fluid on the lungs and heart failure. He needs medical care, fast. Get on the satphone to 000 and plan an ambulance pick-up point. The Australian Resuscitation Council (ARC) recommends bathing the wound site with vinegar, although its efficacy is debatable with this bastard jellyfish.

While you’re waiting for the ambulance, spare a thought for Dr Jack “Handyside” Barnes. In 1965, in the course of research into box jellyfish venom, Dr Jack captured two irukandji, convinced they were the culprits menacing oceangoers north of Cairns. Like all good captains, he wanted to make sure his crew was safe and decided on a spot of DIY immunisation. Assembling his crew (one of them his nine-year-old son), he gave them each a lash of irukandji tentacle then did himself. Within minutes, all three were being rushed to hospital with classic symptoms. No-one died that day, but irukandji have claimed more than a few souls over the years. Beware and wear protective clothing in the water at stinger time.

EXPOSURE: THE OBVIOUS ASSASSIN

Those poor bastards of old would crew a wooden ship on long open-ocean voyages fuelled by diluted rum and weevil-infested biscuits. Their exposure to the elements was extreme, mortality rates were high and the ship’s surgeon or “sawbones” was more capable of cutting bits off than fixing problems. Today, conditions are much kinder, but even short exposure to cold water or harsh sunlight can injure or kill the weekend warrior in a 6m battlewagon.

Hypothermia (when core body temperature drops below 35°C– normal is 37°C) triggers shivering and adrenaline release, increasing your metabolic rate by up to five times. Peripheral blood vessels shut down to limit heat loss and shunt blood to your vital organs. As temperature drops, other organs cease functioning, shivering stops, muscles stiffen, the heart slows and can go into fatal rhythms, brain function declines and death follows.

In nearly freezing water, you’ve got less than 15 minutes, but even in water to 26°C, a few hours’ exposure can be enough. Staying warm is much easier than getting warm, so suit up. If your mate is cold, get him out of his wet gear and out of the wind. Wrap him in dry blankets, stash him in the warmest spot on the boat and lay on the hot drinks (or hot pies).

Sun exposure is the other main risk faced by boaties. Two out of three Aussies will develop a skin cancer by age 70 and I’d bet this stat is worse for fishermen. Almost all these cancers are due to sun exposure. Sunscreen and sun-protective clothing will reduce this risk significantly with SPF30 filtering more than 96.7 percent of harmful UV rays. Get a Buff, sunglasses, a legionnaire’s hat, a long-sleeved shirt, gloves, long pants, boat shoes and a bottle of Cancer Council-approved sunscreen. Your skin will thank you for it and so will your grandkids. Basic sunburn simply needs cooling/soothing creams and time to heal. Remember: each individual sunburn increases your chance of developing skin cancer.

The cause of death of most pirates who weren’t hanged, massive blood loss from any cause will kill you if not treated quickly. For modern salts, the biggest causes of this are shark bites, propeller injuries and accidental impaling by a wayward spear. In the past few years, there have been a number of tragic deaths from uncontrolled bleeding in Australian waters.

As blood loss continues, the limited remaining blood cells cannot cover the extra workload and less oxygen is transported to vital organs. Life is not compatible without oxygen. On the water, your mate’s claret mixing with the bait and brine, you need to act fast. Stopping the bleeding is the priority. Put pressure on, or just above, the bleeder, using your fist or knee if required. It will hurt like falling on barnacle-covered rocks if your mate is conscious, but it’s a life-saving manoeuvre. If there’s another crewman, get them on the satphone to 000 to arrange immediate transport to hospital – they can also tell you where to put the tourniquet. Don’t use a tourniquet if bleeding control can be achieved by other means – it’s a final measure and potentially very dangerous. If you can control the haemorrhage, hang tight, follow advice from the retrieval coordinator and wait for the rescue crew. They’ll bring equipment and possibly blood. Survivors are alive today due to quick-thinking mates or good Samaritans.

Blokes die on average four years earlier than women, partly due to a reluctance to seek medical help or use preventative- health strategies. All men should have a healthy relationship with their butcher, their fishmonger and their GP. Find one of each you trust and you can look forward to more time on the water and with your family.

Sources: Electronic Therapeutic Guidelines, Australian Resuscitation Council, Advanced Trauma Life Support manual.

WORDS by Dr Marlow Coates, FACRRM, FRACGP, JCCA Anaesthetics Accredited, MBBS, BPhty, SMO Torres and

Cape Hospital and Health Service

Recent Comments