This Hawkesbury River legend has been snaring crustaceans for more than 50 years — but he isn’t ready to hang up his crayfish pots any time soon. Keith Sewell can pilot his 115HP Yamaha powered tinnie at more than 30 knots, steering with the tiller between his legs while lighting a cigarette. It’s not easy — we tried. He’s in his seventies, but still gets out most days to check his crayfish and mud crab pots dotted around the mud flats, reefs and rocky fringes of the Hawkesbury River system.

Keith got his commercial fishing licence in 1962, following in the footsteps of his father. His old man was a descendant of Irish convicts, which might explain Keith’s disdain for officialdom. Fifty years ago, commercial fishing life was a simple affair. The boats were slower and made of timber. There were no mobile phones and a bloke wasn’t required to log on every morning to record his fishing activities, as is expected today. Keith laments the way the commercial fishery is being managed, saying, “It’s a great nation, but we’re fucking it up with bureaucracy”. These days, he spends a lot of time just trying to decipher his mobile phone, let alone the regulations. “I’m a fisherman, not a computer expert, I left school at 14. With this modern technical age, we’ve lost touch with common sense.”

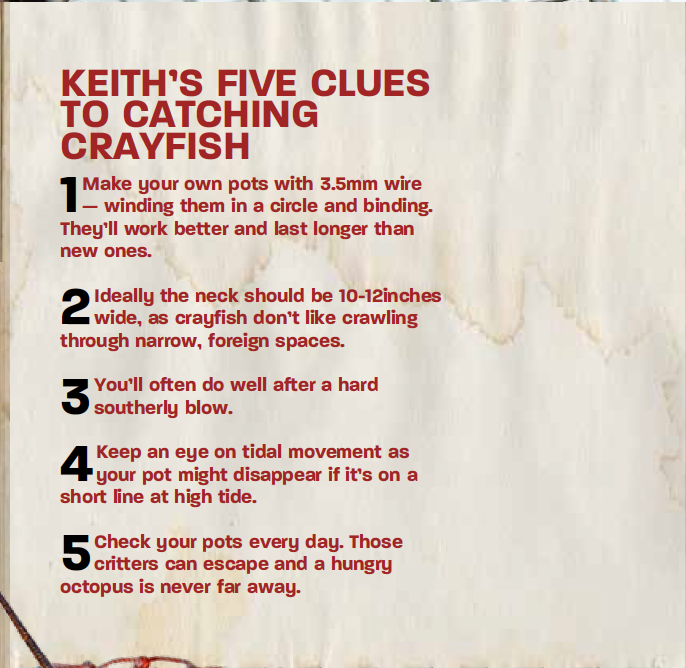

But some things that haven’t changed much over the years like the handcrafted pots Keith twists from 3.5mm, 8-gauge wire. He binds them in a circle and reckons they work better and last longer than new pots, although good-quality steel is getting harder to find. A downside of making good pots is that unscrupulous fishos nick them. Thankfully, Fisheries have his back — they recognised one of Keith’s lobster pots and returned it to him. Apparently, some teenagers were using it as a blue swimmer crab trap.

COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN

Despite Keith’s misgivings about the red tape wrapped around commercial fishing, crayfish trapping still gives him a great sense of fulfilment. He says it’s a healthy lifestyle noting, “most of the old fishermen who were around when I was young lived into their nineties”. He’s learned to read the weather patterns and knows how they impact on fish. The “thrill of the kill” — and the rewards that come with a pot full of crustaceans — also keep him motivated. Every day the weather allows him, he hauls those pots into his tinnie and rebaits them. His crays are measured, tagged, weighed, covered in wet sugar bags then hauled to the Sydney markets on the back of his old LandCruiser ute. At the markets, the crays are sold to restaurants and fish shops around Sydney.

The typical price is $65-$100/kg, a bit lower for mud crab. His biggest payout was in 2013, when a shortage of live crayfish and strong demand from the Asian markets drove the price to $116/kg.

POT OF GOLD

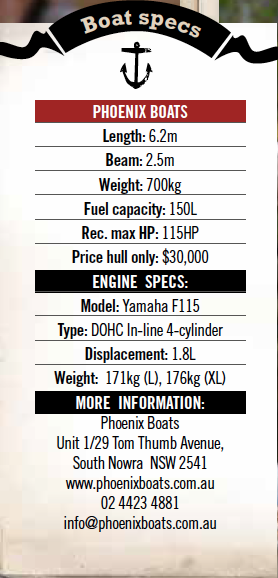

He once counted 53 crayfish in a single pot, the impressive haul helping him fund the upgrade from his beat-up, 30-year-old Quintrex FishFinder to a shiny new 6.2m Phoenix. Built in Nowra, the open tiller-steer tinnie features 5mm plate on the bottom and 4mm on the sides, with a self-draining deck that sits six inches (15cm) above the waterline. Keith’s hankering for the old ways was imprinted on his new boat when — after spotting a Viking longship in the Australian National Maritime Museum — he asked Phoenix to incorporate some of the Nordic chine shape into his vessel. He reckons it adds strength and efficiency through the water.

Keith says his boat is, “made to move a lot of gear quickly, when the situation arises”. Accordingly, it’s fitted with a 115HP Yamaha fourstroke. He’s always been a Yamaha man because he reckons they go forever. That 40HP Yamaha with 5000 hours on the clock sitting on the back of his weather-beaten Quinnie is his proof. While admitting his new Phoenix is a little overpowered, he reckons that the 115HP uses as much fuel as his 40HP does over the day, and that he’s covering far more ground. Another win for big horsepower.

DOWN TO THE LOBBY

The Captain was gobsmacked to discover that there are no actual lobsters in Australian waters. True lobsters only live in the Atlantic. The imposters crawling around ocean floors off the Australian coast are actually rock lobsters, aka spiny lobsters — often mistakenly tagged “crayfish”.

It’s complicated. Lobsters, crayfish and rock lobsters are all aquatic arthropods. They all have an external skeleton and segmented bodies, which lumps them in the crustacean class. But that’s where the party stops. The obvious points of difference are that Aussie rock lobsters don’t have claws and most of their succulent meat is in the tail. The basic rule of thumb for fishos in this part of the planet is as follows: If you caught it in salt water and it has no claws, it’s a rock lobster. If you caught it in fresh water and it has claws, it’s a crayfish. Before you go figuring you’ve got it all sorted, chuck this into your think tank: yabbies are a kind of crayfish, but Balmain and Moreton Bay bugs are also known as “slipper” lobsters — hillbilly cousins of the rock lobster. They’re a staple feed for octopus, Asian restaurants and generous mums preparing the family Christmas feast.

LOBBY SPECS

Lacking claws, the rock lobster relies on its body armour, called a “carapace”, which has two sharp spines and hundreds of smaller thorny nobs on its back, to keep predators away. And it’s fitted with a car alarm — rubbing one of its antennae against a soft part of its carapace to produce a screeching sound when it gets a dose of the shitscareds. Those long antennae are also employed for navigation and communication. It’s got horns, eyes on stalks and five pairs of legs, which may seem excessive, but rock lobsters tend to lose limbs and antennae rejecting dinner invitations with other fish. Handily, they can regrow them.

Rockies hoover the sea floor for whatever they can scavenge. They’re particularly partial to snails, clams, crabs, small shells and sea urchins — but they’ll also snarf up coral algae and detritus— dead/dying marine matter. Home is in rocky crevices or, in tropical waters, the nooks and crannies of coral reefs.

LOBBY LOCATIONS

For commercial fishos, the southern rock lobster, caught in south-eastern Australia, and the western rock lobster, found in southern WA, are the bomb. The southern rockie hangs out in a variety of reef habitats, from shallow rock pools to the continental shelf. Their colour varies from reddish-purple in shallow water to purple and a buttery yellow further offshore. About eight species of rock lobster call WA waters home, but the most abundant — and commercially valuable — is the western rock lobster. They mainly inhabit a stretch of the continental shelf off the coast between Perth and Geraldton. A lucky lobster can live more than 20 years reaching up to 5.5kg. In warmer water, they mature at around five to six years old, at about 70mm in length.

LOBSTER LOVE

As with most species, love can be a complicated affair for the rock lobster. Feeling the call of the wild in late winter/early spring, the male attaches a blob of sperm, a “tarspot”, between the lady lobster’s back legs. When females release their eggs, they scratch the tarspot, fertilising the eggs as they’re carried backwards before attaching themselves to sticky fine hairs beneath the lady tail. Females carrying eggs are known as “berried” (and untouchable to fishos).

When the eggs hatch, they release larvae, called phyllosoma, which depart for a gap year drifting 400–1000km offshore. For most of the lobstery planktons it’s a one-way ride. Those that survive morph into transparent minilobsters, or pueruli, carried back to the coast by wind and tide.

This trip is equally risky. Those that do arrive at a desirable onshore reef location grow into juvenile rock lobsters via a series of moults. Turning a distinctive red colour, they become bottom dwellers, bulking up for the next three or four years.

This is when they undergo a synchronised moult, their colour changing to a creamy white. These “whites” then go nomad. Once their new shells have hardened, most migrate west into deeper water, resettling on deeper reefs. A brave few head north in groups, travelling at night along the continental shelf to find suitable spawning grounds, sometimes 100km from “home”. That’s when the lobster love starts all over again.

Recent Comments