Science under the Southern Sea Deakin University marine biologist Associate Prof Daniel Ierodiaconou – aka “the fish hypnotist” – spends a lot of time on, in and under the sea. He and his team of sea scientists have been putting together 3-D maps and video of the underwater world off the Victorian coast – charting the topography of undersea valleys and mountains, ancient river systems, volcanic cones and lava flows. They’ve also been checking out the marine life and mapping sea floor habitats. He and his crew have now charted more than 5,500sq km of Victorian coastal waters. Using acoustic multi-beam sonar technology, the next phase of the project will provide a detailed picture of seafloor habitats, from Moonlight Head to Aireys Inlet, to depths of more than 100m.

“We’ve uncovered seascapes we didn’t know existed, from giant kelp forests to extensive sponge gardens. Some areas rival the corals of the Great Barrier Reef in terms of their complexity, colour, beauty and marine life,” the prof says.

Ierodiaconou has always been fascinated by the sea, spending childhood holidays at Lorne, watching his father spear fish and dive for abalone. He completed his first Pier to Pub swim at the age of 10 and was scuba diving by 14. After high school, he studied marine science at Deakin University, Warrnambool Campus where he ended up on the staff list. Speaking of marine life, the prof is also partial to a spot of rock lobster.

SO WHY DO WE NEED ALL THESE UNDERWATER MAPS?

“First, we collect physical information to characterise the seascape, then we use this information to prioritise sites to obtain biological collections. We then integrate this information to make predictions about species distributions, abundance and connectivity of habitats. For the first time we have an accurate and comprehensive picture – including hotspots for marine plants and animal communities.

Many of the locations we’re currently working in haven’t been visited since Matthew Flinders circumnavigated Australia and took depth readings from The Investigator in 1803. Coastal marine habitats are under threat from human use and a changing climate, and without this data it’s difficult to make informed management decisions. For example, in some areas, marine communities are changing due to climate change and range expansion of certain species. The research helps us understand the reef so we can sustainably manage our marine estate.

What we’re doing now is important, but the real value will be in 10 , 20 and 50 years’ time when the data is revisited to determine our impact. I also hope my research will encourage the conservation and fisheries sectors to work more closely together. I feel we’re making headway. Our data has been used to investigate fish-habitat relationships for Parks Victoria in marine parks – while also working closely with commercial fisheries to investigate habitat connectivity for rock lobster and abalone.”

WHAT’S SO GREAT ABOUT THE SOUTHERN REEF?

“The Great Southern Reef extends along the southern coastline of Australia. Scientists estimate it to be worth over $10 billion dollars to the economy, it’s home to a bounty of marine life in its cool temperate water – good news for recreational and commercial fishers – including the abalone and southern rock lobster that thrive in its seaweed forests.

The reef was born about 60 million years ago when Australia started to separate from Antarctica. As it moved north, the southern waters became geographically isolated, the distance from other continents and the nature of ocean currents allowing species to evolve on their own. The upshot is that nearly 80 per cent of the plant and animal communities in these waters are found nowhere else. Victoria’s coastal marine habitats are home to a rich diversity of flora and fauna, which in turn support commercial and recreational fisheries, aquaculture, gas production, navigation and whale watching.

We’re on the doorstep of one of the largest upwelling systems in the world. In summer, prevailing south-easterly winds drive deep cool nutrient-rich water to the surface. This is the larder supporting commercial fisheries, one of Australia’s largest gannet colonies and Australian fur seals – not to mention the annual blue whale visits.

It can be a challenging place to work. But if you get it right, the ocean is a bounty – from kingfish to southern bluefin tuna, quality bottom fishing and yes, rock lobsters in abundance.”

TELL THE CAPTAIN A WEE BIT MORE ABOUT THOSE DELICIOUS ROCK LOBSTERS

“The prized southern rock lobster makes its home in the crevices of the southern reef surrounded by their favorite foods and algae – there’s a reason Phyllospora comosa kelp is known as ‘crayweed’. Their life cycle is complex. The larger the female lobster, the more eggs she can store under the tail. Once hatched, lobsters are at the fate of ocean currents for nine to 24 months. They can travel quite a way in that time – the lobsters on a single reef may be related to larval supply thousands of kilometres away. They go through a number of biological changes (metamorphosis) before they settle. Most people don’t realise the legal-size lobster you see in the shops or in the water could be 10 years old and they get much bigger than that. This is why management of the fishery is so important – what we do now will impact stocks for decades to come.

Catching lobster is not for the fainthearted. Often, to get near a lobster a diver has to squeeze into tight cracks – a bit challenging in a rolling swell. Amateurs often get stuck. The tendency is to lunge quickly, but this often leaves you with a handful of antennae. A lobster needs these to feed, so this damage limits the chance of their survival. The key is to go slow and ensure you get a grip on the base of the horns before engaging. Hold on tight and adjust your position to ensure you can extract your dinner.”

STABICRAFT TO THE RESCUE

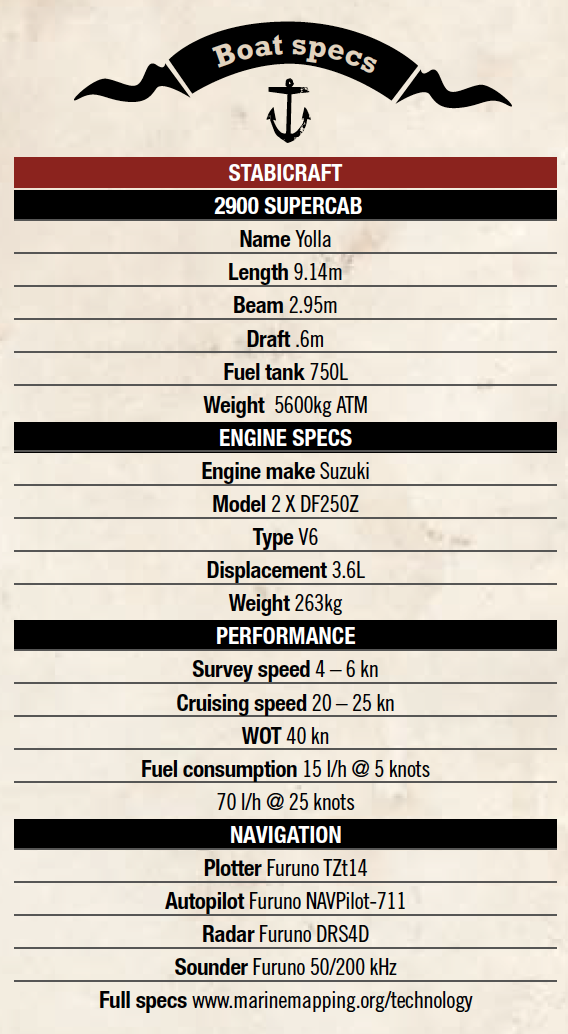

Always fascinated by the sea, the prof developed Deakin’s purpose-built $650,000 research vessel Yolla, which boasts the most advanced sonar system in the world – the latest-generation multi-beam sonar system is capable of measuring 400 beams up to 50 times a second, that’s 1.2 million soundings a minute – to image the seabed, and remotely operated cameras that are tracked underwater to provide video footage from deep below the surface. The vessel the scientists chose was the custom 9,2m Stabicraft. Why?

“The key is seaworthiness and stability. We don’t tend to work a lot in bays, so we need something that can handle tricky conditions in the Southern Ocean. The Stabi provides us with a stable platform to get the work done. For example, we spent six weeks mapping off Wilsons Promontory Marine National Park, the southernmost point of mainland Australia. We had tried to map the area twice before with larger ships, but were blown out. Most of the research vessels with the type of kit we carry are 25m-plus. We wanted to be able to do the same quality of work, but on a cost-effective platform, and needed to be able to get to sites quickly to maximise weather windows and get out of the way when it blows. The Stabi’s trailability is an advantage for mobility, and the twin Suzuki 250s allow for speed to 40 knots while also generating the juice to run a full computer rack and scientific gear – data-capture speed at six knots uses nine litres of gas an hour.”

THERE’S SOMETHING DOWN THERE

“This region is also known as the Shipwreck Coast. It has some of the largest waves on Earth, treacherous coasts with high cliffs and limited safe harbour. Navigating these treacherous waters was a bit more of a challenge in the days of sail and steam, accounting for the more than 600 known wrecks along the coast.”

In the course of their research, the prof and his team have added another name to the ‘known’ list. They imaged the MV City of Rayville, the first US vessel sunk during WWII, was blown up by a German mine in November 1940, off the coast of Cape Otway, in more than 70m of water. With their high-tech sonar and remotely operated vehicles (ROV), the scientists were able to snap the first detailed images of the wreck.

“It was very exciting to see the City of Rayville for the first time. Sponges and sea whips have colonised the exterior of the wreck and the hull is an artificial reef, attracting and providing habitat for fish.” As well as old shipwrecks, the prof’s underwater spies also spotted the ‘Drowned Apostles’ – shorter submerged cousins of Victoria’s famous Twelve Apostles tourist attraction. The 7m limestone columns sit 50m under the surface about 6km offshore. Fascinating stuff, but what really turns Dan on is the diversity and bounty of marine life. This is the ideal place to be a marine scientist.

Recent Comments