Abalone — most people wouldn’t know what it was if they stubbed their toe on it at the beach. Underneath an iridescent mother-of-pearl shell is a muscly piece of meat about the size of a teenager’s fist. This magnificent mollusc is so prized in Asia that most of these babies have “export only” stamped in their passports at birth — point being, you’re unlikely to spot them on sale at the seafood counter in Coles or Woolies.

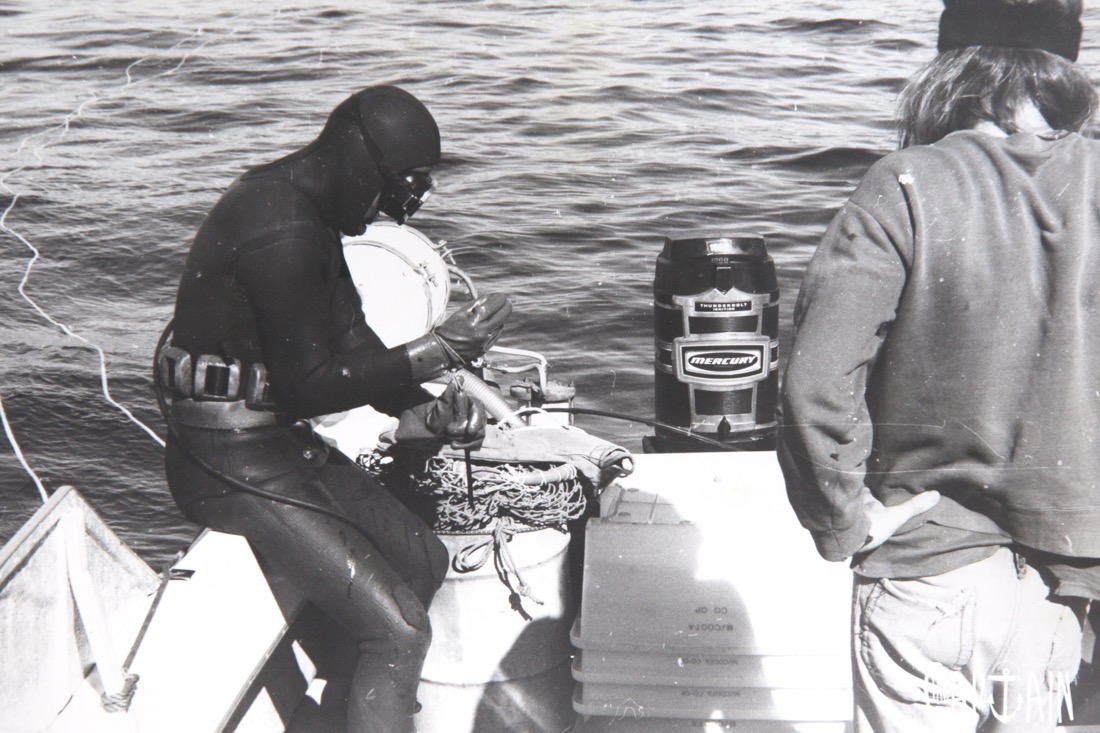

The abalone men of Mallacoota in Victoria’s Gippsland, will see hundreds a day, maybe thousands a week. Abs cling to the rocks and reefs using a suction-pad “foot” — coming out at night to feed on algae. Rubber-clad divers use knives to scrape them from their perches, typically relying on surface-supplied air “hookah” systems from a drifting or anchored boat operated by a deckie. It’s hard yakka. Along the eastern coastline, the conditions are often shitty — cold and windswept. It’s not uncommon for divers to spend five or six hours a day in wetsuits they also have to pee in. After harvesting, the abalone are shucked, or delivered live to the co-op in Mallacoota. They’ll be shipped off to adorn Asian banquets, while the divers head home for a long hot shower.

Now, although abalone is rumoured to be an aphrodisiac, the men from Mallacoota don’t hunt them for their amorous assistance (although we’re sure one or two have attempted to verify the rumours), they don’t even do it for the taste. To a typical Mallacoota abalone diver, the abalone is merely a snail on the ocean floor; it’s the means to an end. That “end” is enjoying a life on and under the water, free from unscrupulous wankers in white collars, traffic jams and soccer mums in SUVs.

Abalone fishing is also a lucrative business that affords the men of Mallacoota a lifestyle most of us can only dream about. On their days off, they can be found drifting the expansive Mallacoota lake and river system for giant flatties or bream, or perhaps backing up to bait balls and pitching live-baits to stripe and black marlin in the cobalt-blue offshore currents. You might find them hunting sambar deer with high-powered rifles, or chewing up gravel tracks on 450cc dirt bikes. At night, you’ll almost certainly find them at the local pub engaging in high-powered drinking sessions, regaling each other with yarns about the capture of the day. The Captain is seriously contemplating keeping this kind of company on a more regular basis.

IN THE BEGINNING

But abalone diving is more than fast living funded by slow snails. The industry has spawned an armada of offshore powerboats, many of which adorn the pages and videos of The Captain. Brands like Edencraft, Cam Craft, Whitepointer — and to a lesser degree, Haines Hunter, Cootacraft and Shark Cat — exist today because of the demand for these tried-and true hulls for commercial abalone fishing. (Captain’s note: for the record, in the late 1980s, Haines Hunter was dead and buried until Edencraft revived these legendary old hulls, largely for commercial abalone applications.)

To understand where it all started, The Captain’s crew headed south to Mallacoota, on the coast just south of the New South Wales/Victorian border. We caught up with two generations of abalone fishermen, Grant Shorland Sr and Grant Shorland Jr, a father/son tag team who specialise in high jinx above the seas and snail snaffling below.

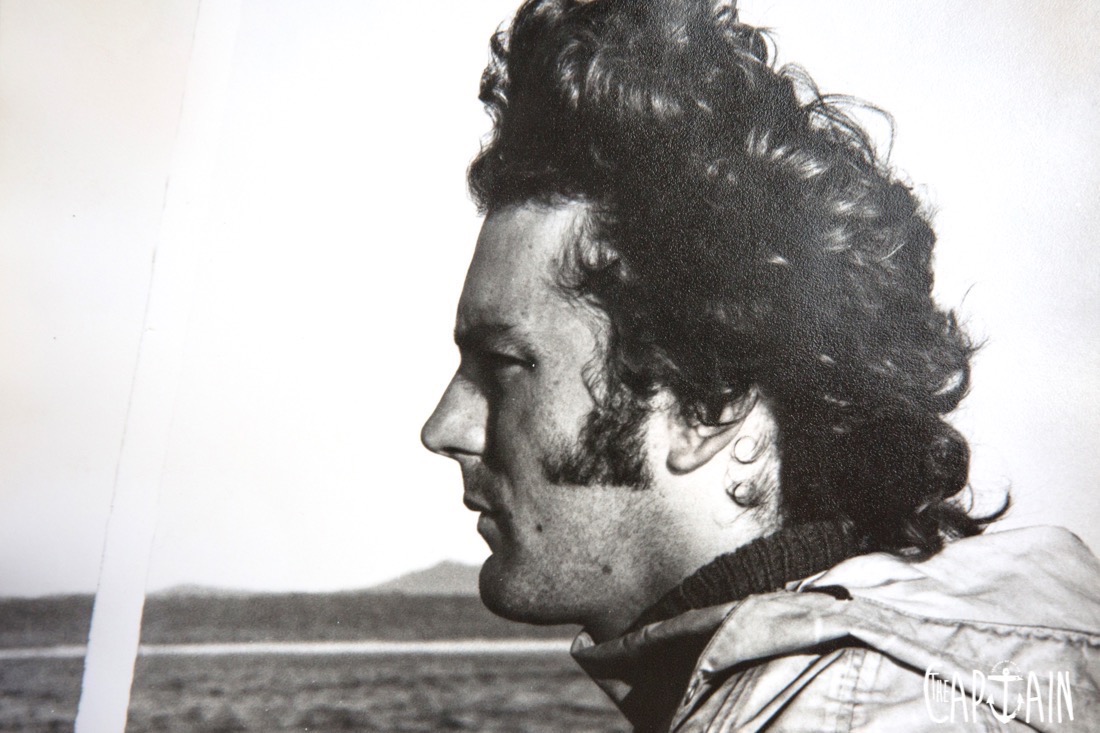

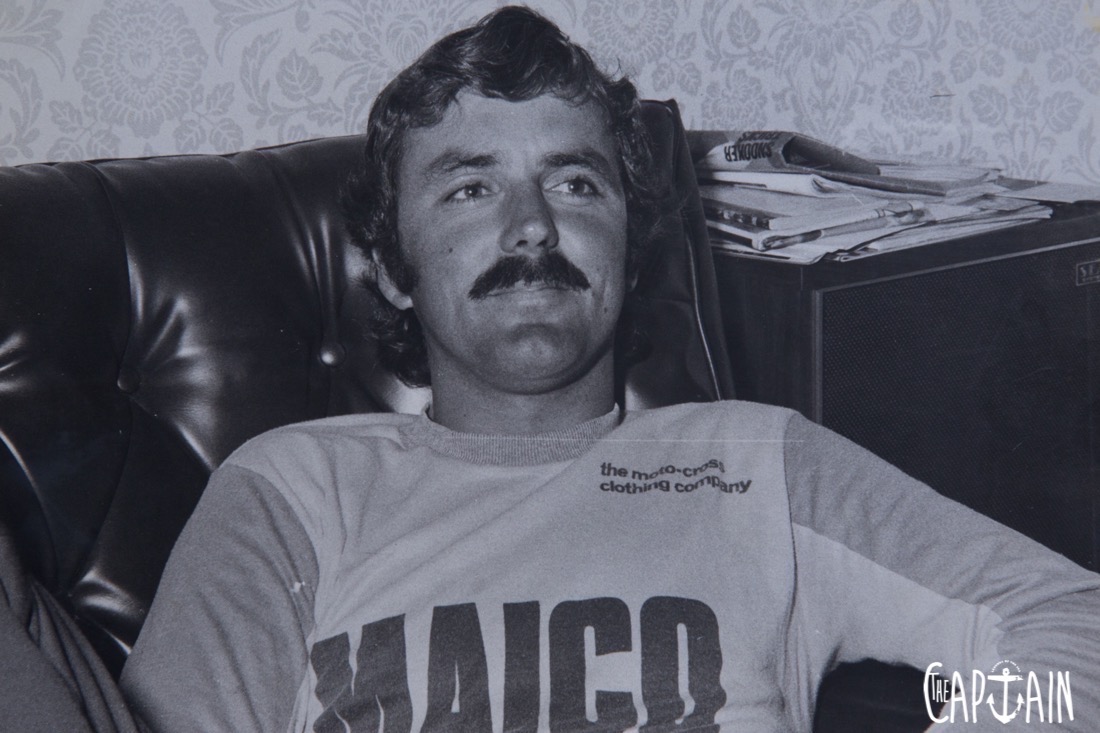

Grant Sr has just turned 70, but you wouldn’t know it. He sits upright and proud on a stack of abalone bins at the Mallacoota co-op, gazing at the tough commercial-class Edencraft Formulas and Offshore models, Cootacrafts, Bass Strait beauties, Haines V19s and old Shark and NoosaCats. His appetite for life and wicked sense of humour keeps pace with son, as does his liver, which gets regularly tested. The idea of a life by the sea started for Grant Sr when, as a 19-year old advertising “executive” in Melbourne in 1966, he noticed his boss’s pay packet was bulging at the seams — the big kahuna was earning $60 per week, compared to Grant’s paltry $24. “I’d take my chick out and blow the whole lot in one night”. Then he had to hitchhike to work on Monday.

Then, on a water-skiing trip to Mallacoota, he spied a few local Maoris playing guitars in the pub, drinking champagne and having a whale of a time. On further investigation he heard divers were earning $100 a day, so he jumped on a 21ft stern-powered Bertram and went to sea as an abalone sheller, earning $20 per day.

The first day his skipper headed to Little Ram and hauled a mountain of abs. “I spent nearly half the day, cleaning the bastards,” he says. His pay packet had expanded a little, but it still wasn’t enough. He slept in a canvas tent, usually with uninvited funnel-web spiders for company. On a good night he’d sleep at the pub. The weather often kept the diving fleet off the water, so he picked up extra work behind the bar — at least he didn’t have to hitchhike to work anymore — and eventually he saved enough to buy a Caribbean Mustang with a 100HP Mercury.

AN INDUSTRY IS BORN

Back then, there were about 100 divers fishing in 50 or so boats. There were no licences to speak of. Instead, there was a professional fishing licence costing the grand sum of $7. It entitled the owner to catch an unlimited number of abalone. “There were no quotas.” Grant says. “The abs were much bigger and we were bringing in 1000lb per day”. The local authorities eyed the growing trade with interest and slapped a $200 licence fee on the snail hunters. “Half the guys left. Some went down to Portland and the central zone. We hung about and it was the best thing we ever did.”

Quotas were eventually introduced. By Grant’s own admission, he was overfishing. “I was one of the worst to overfish. They used to call me Dago — I’d go out early and come back late. I’d fish Marlo and Mallacoota and have a vehicle and boat at each end. We fished 40 days more than the other guys and I ended up buying a plane, which I paid off in six months.”

Grant was catching about 75 tonnes a year back then (Captain’s note: his yearly catch now sits at almost 40 tonnes, as per his licence). The money was good, but the adventures were even better for Grant and the abalone boys. He bought a block of land and a caravan. The well-worn Mustang was replaced by a V19 Haines Hunter fitted with a wave-breaker, its fuel lines fed straight in to a 12-gallon drum of BP Zoom.

“It was like living two worlds. I had the world up here and the world down there. Every day I went out it was different. Some days were like diving in a bottle of gin. I could look up in 80 foot of water and see the numbers on the side of the boat and the deckie looking over the side. You’d glide to the bottom and it was just deluxe. Other days, you’d bump into the bottom and it was shithouse. We’d go down to Cape Everard — it was like travelling to the end of the world, a real adventure. Now [travelling that distance] is nothing. Initially, we didn’t even have an echo sounder. We’d have a look around clear water, jump in, see a bit of reef.”

It was a learning experience for many of the divers. If they were lucky, they had a crash course in a local swimming pool before jumping in among the underwater ledges, boulders and kelp forests swaying in the currents of the Tasman Sea. “We had terrible diving gear, garden hoses to breathe through, no filters — we were absolute guinea pigs. I don’t know how we stayed alive.” But stay alive they did, and the pay-off was a wad of cash or a big fat cheque back at the ramp.

“We’d come into the wharf, and the buyers were lined up — they used to give us cash. There was a sandwich board for the Chinese. Tom Bidwell from Cann River was there — he used to carry a gun. Switzers came down from Eden every day with a flattop semi-trailer. All the abs were drained on the wharf and salted and tarped up.”

YOU’LL BE NEEDING A BIGGER BOAT

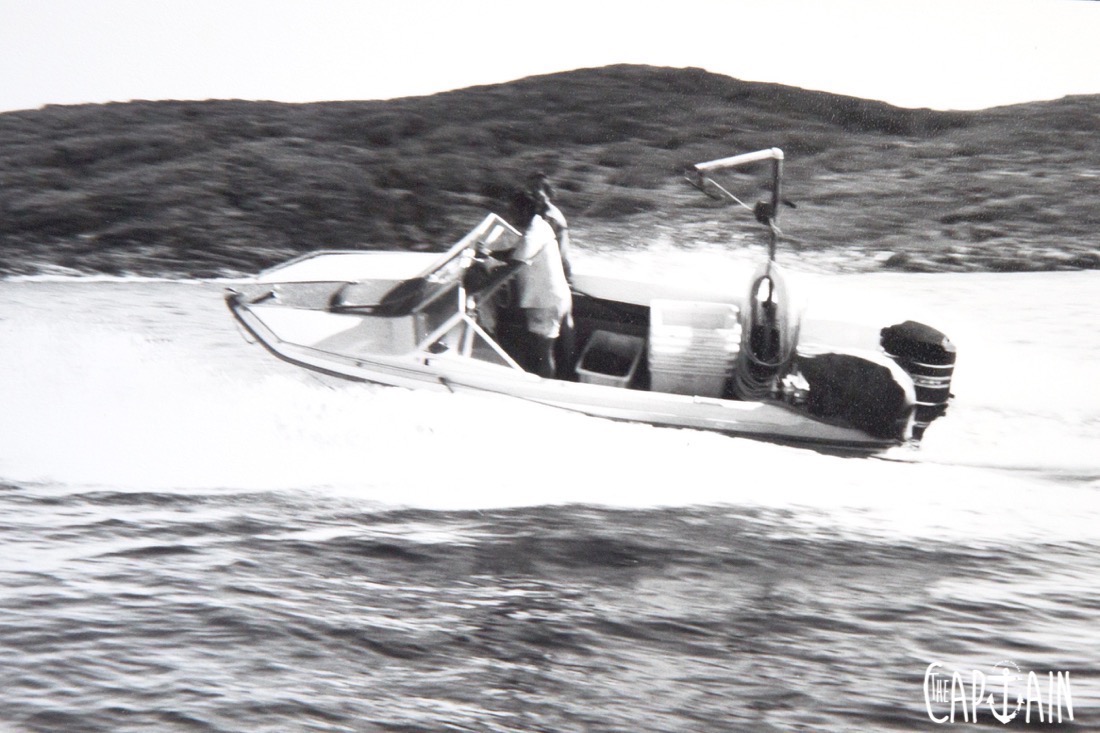

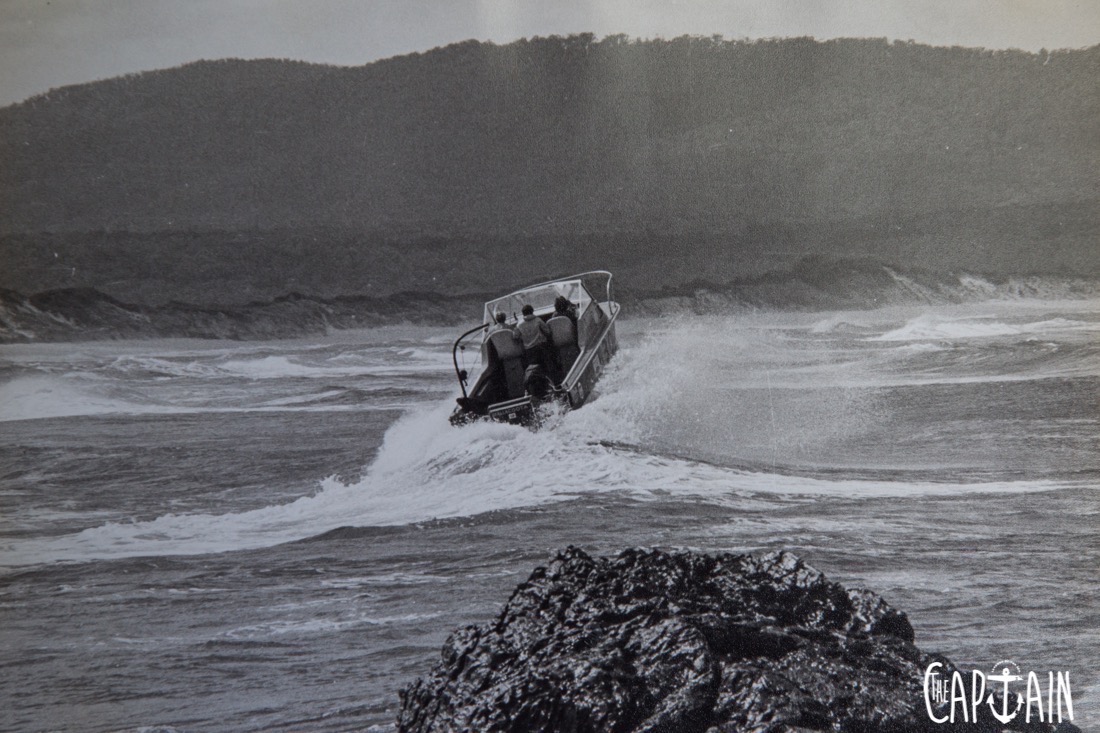

The demand for bigger payloads increased, as well as the need to dive in rougher conditions. One day, Bruce Harris came to town and launched a 20ft Shark Cat side-on to the breaking waves for all the abalone divers to observe. It was a persuasive sales pitch and convinced several locals to trade up on the spot. The hulls on a few of the original deliveries caved in under the immense weight of the abalone, so Bruce’s crew came back to town and reinforced them all at the same time. Nobody ever complained about a crushed Shark Cat again. Grant Shorland took a little while to be convinced, but eventually bought himself one after a trip to Labrador, birthplace of the Shark Cat.

“I went for a ride with Bruce’s offsider, Basil Noonan. He was a big, beefy guy who did the shark-net contracting on the Gold Coast. We went up through the Broadwater, up to Jumpinpin and out through the bar. He pulled up in the white water, turned the cat sideways and asked, ‘Do you want to have a drive?’ Then he pulled the steering wheel fair dinkum off the shaft and handed it to me. This big sea crashed into the boat, then another one hit us. I couldn’t believe it.”

After the water drained out the rear scupper Grant handed the wheel back to Basil, paid his deposit and ordered one. “I could go anywhere in that thing. The ride on the Shark Cat was unbelievable. We’ve been in some enormous seas, we’ve had it laying on its side in a big sou’ easterly and it flopped back on its wheels again and again.”

The Shark Cat also proved a formidable racing boat. “We decided we’d have a go at ocean racing,” Grant says. “Bruce Harris was terrific giving us advice. We took the windscreen off and put in the biggest engines we could get — 150HP, straight six-cylinder Mercury outboards with stainless-steel props. We pulled the engines apart, straight out of the box and blueprinted them at Bruce Osborne’s shed (also the local BP service station). He did a fantastic job on those engines. They were humming — vented cowls and all.” “We did the first Sydney to Newcastle, heading off from Rose Bay and out through the heads. It was pretty rough and blowing hard. There’s a buoy about three miles out, straight off the heads. We passed Arnold Glass loping along in his Cigarette. We just gassed it in the poor little Shark. Arnold got the shock of his life when he saw this old fishing boat, completely airborne. We beat him around the first buoy, but then he put the hammer down and dusted us with 1000HP — we only had 300! We also had some successful races around Port Phillip Bay. The Shark Cat was in its element in the short chop and shallow water.”

Between racing adventures, Grant was earning enough to convince his girlfriend to be his wife. The honeymoon was held in Mallacoota. Grant had a ripping time, piling his dirt bikes in the Shark Cat and blasting through the trails and beaches of the national parks with his mates. His wife-to-be was nowhere to be seen and was less pleased with the honeymoon celebrations. “We used to have some fun,” Grant says with a smirk. “There were no police back then. We raced around the lake in boats then raced around the town in our Austin A30s and FE Holdens.”

BUBBLES IN THE BLOOD

Grant’s salty skills and knack for making a buck were apparent. He applied them to scallop fishing, cray fishing and even some offshore work for the gas drilling rigs, skippering a huge Shark Cat along the gas lines looking for damage from trawlers. But he hankered for life under the sea, as well as the financial reward of abalone diving. From 22 cents a pound (half a kilo) in the 1960s, abalone now fetches around $40/kg in shell weight (beach price). An abalone licence can cost up to $6 million, a far cry from the paltry $7 fee in the late ’60s. But it came at a price.

“We’ve all had our scares with sharks, but my biggest scare was when I had a spontaneous embolism. I was 10ft from the surface and couldn’t work my arms — paralysed from the nipples down with this pain like a big bag of spuds on the back of my neck.”

It was not a bag of spuds… it was a life threatening air bubble.

“I had a cup of tea, jumped back in the water. The bubble squeezed down and the pain went away; my arms were working again and I got another bag of abs. When I surfaced for the second time, I realised something was definitely wrong. They put me in the [hyperbaric] chamber at the co-op for the night. The next morning I still had pins and needles and so I was choppered out to the Alfred Hospital and spent 28 days in and out of the chamber while they gradually flushed my system out with oxygen. Now I’m about 90 per cent clear. The specialist said I’d stressed the capillaries in my lung, and created a cavity to let air into my bloodstream.”

So Grant’s days of commercial abalone fishing were over, but he didn’t sit still for long. He gave the keys of the Shark Cat to some lads to dive his quota, and acquired his commercial helicopter licence. He did some charter work and now flies for the Rural Fire Service and National Parks.

“You gotta keep doing things,” says Grant, who still owns several abalone licenses with son Grant Jr. The Shark Cat has changed hands and is now owned by local cray fisherman John Black, but Grant is still ready and willing to jump aboard for a photo shoot or head offshore with the boys chasing marlin.

The Captain salutes you, Grant. But we’re not so sure we’ll be drinking Russian vodka with you in the wee hours of the night prior to an offshore fishing trip ever again.

SON OF A GUN

He’s got a job and lifestyle many young men dream about. He owns cool boats, cool trucks and drinks like a fish. He also happens to earn a living under the water, rather like a fish. But he assures The Captain it’s seriously hard work (the drinking, that is).

Grant Shorland’s riotous laughter cackles through the tin shed of the Mallacoota Co-op. He’s sitting on fish bins between his green-and-gold Cootacraft Gun Shot and a steely black Formula 233 called The Office. He’s telling yarns and sinking beers, two of his favourite pastimes. He’s also pretty handy at abalone diving.

Grant is one of the lucky divers in Mallacoota. His abalone licence was passed down from his father, Grant Sr. But he’s not taking the good fortune for granted. “I was lucky enough to be born into it. The old man was lucky enough to walk into Mallacoota and get into the industry and it’s been very good for our family, and many others as well. I’m very thankful for it.”

Grant reckons having an abalone licence means nothing without putting in the hard yards. With his deckie, he dives 56 days a year to collect 26 tonnes of abalone, five of which he has licence for (his father owns the remaining quota).

“There’s money in everything — in all fisheries. But you’ve got to put the work in; you’ve got to put your arse on the line. If you want to earn money, you’ve got to work for it.”

Grant Sr, known as one of the hardest-working abalone divers in Mallacoota during his diving stint, is also his boss — and his greatest inspiration. “If I could become half of what he is in this day and age, it would be unbelievable,” says Grant Jr. “We’re best mates, we fish, we get on the piss, we have adventures — good dad shit. He gives me a job and a lifestyle, so I’m pretty stoked.”

According to Grant, diving isn’t the only skill required to dive for abs in Mallacoota. “A good ab diver is one who can stay until after 2am in the pub and then go out and get 500kg the next day.”

Grant describes Mallacoota as “the final frontier”, and he wouldn’t want it any other way. “We’ve got a good lifestyle. I can look out my window at the lake and ocean at the same time. If I want to go to the beach, I go to the beach. If the weather is good, I can go ocean fishing. If it’s bad, I can go up the lake and I’m still catching fish. If I want to shoot deer or go dirt-bike riding I can do that…”

Grant’s train of thought suddenly slams to a halt. “I don’t really want to sell the place too much because I’ll get more people coming here, and it’s not what I’m about.” Grant has had his fair share of drama, but it didn’t involve the bends (like his father) or even a shark. It happened on a calm (or so he thought) day. His Cootacraft Gun Shot, Pearl Moon — the boat he helped build from start to finish — was almost crushed on the rocks and scattered around the ocean floor with the sea snails he hunts.

“It was a bit of a stuff-up. We had 2.5 tonne to catch and were behind schedule. It was a dead-flat day and we only needed three more boxes to get 600kg. I cruised into the bommie (bombora) and was about to go backwards through the dive door when the deckie shouts, ‘Look out!’

I turned around as this wave came over the back of the boat and threw me forward. Boxes of abs went everywhere — it was panic. Then another wave smashed us. It was a three-set and bang! — we were hit again. I yelled, ‘Hit the bilge pumps!’ but the deckie yelled back, ‘The hoses are caught around the motors’.

I screamed, ‘Just cut ’em! Go, go, go! We’ve gotta get out of here!’ The motors seized on the third wave. It was all over then and I couldn’t believe my boat was sinking. I started chucking boxes of abs over the side then jumped on deck. The water was coming in through the dive door and I told the deckie to abandon ship.” Before any tow ropes or safety gear, they got their cameras out!

Grant and his deckie were now treading water next to the sinking boat. They had no flares, no phones, no EPIRB — just the packet of rollies his deckie was holding above his head.

“It was one of the best survival tools we could’ve had. We could have just climbed on the rocks and smoked durries until we were rescued.”

There was no need. Fortunately, just when Grant’s boat started crunching, another dive boat rounded the corner and spotted them. It was ZEK, another green-and-gold Cootacraft, skippered by Dale Winward.

Grant continues the story. “I said, ‘We’ve rolled, give us a tow’, but before any tow ropes or safety gear, they got their cameras out! By now I could hear everything smashing and breaking, so I rang Mark ‘the Russian’ (head honcho of Cootacraft boats) and asked him, ‘What’s the wait on a new boat?’ He replied ‘Two years’. I decided we were going back for this one!”

The boat was eventually towed out and rebuilt with a new wave-breaker, new running gear and new twin 90HP Suzuki motors he services himself. They’ve never missed a beat, Grant reckons.

“It’s a grouse commercial boat — love it and wouldn’t have anything else. It’s easily towable; you can’t break them — I’ve tried. They’re super-soft, a big small boat, there’s nothing compares for its size. We load ’em full of abs every day and get back (almost) every day — we’ve put 1200kg in it.”

Whether diving or fishing, Grant loves being on the water, and it wouldn’t be an understatement to say his gamefishing exploits are establishing Mallacoota as a marlin destination — at least by Facebook standards. In the past few months (February and March), he’s been putting up numbers that would make commercial operators blush. He fishes in a Grady-White Journey 258 known as Cubin’, fitted with twin 150HP Yamaha four-strokes.

On choosing the smooth-riding American hull, Grant says, “I was going to buy an Edencraft Formula 233 and use it as a workboat and gamefishing boat, but I’d be out there in my work boat going, ‘This is shit — no roof, sunburnt, no seats and a dead abalone somewhere in the back’. (With the Grady-White) I just hook it up, press buttons and gaffs come out. It’s chalk and cheese.”

BASTARD SEA URCHINS

Despite his carefree, fun-loving nature, Grant still concerns himself with the sustainability of the abalone industry — sea urchins in particular. “We’ve got dramas with the sea urchins. They live in the same areas as abalone and compete for the available food supply. Once they come through, they turn everything to ‘barrens’ or ‘white rock’. Abalone don’t come to areas where urchins have fed.”

Grant says they are culling sea urchins to get the ground back. “It’s been a major project for us, largely funded by the licence holders in the Eastern Zone, stretching from the NSW/Victoria border to Lakes Entrance. We don’t cull them out of the feed line in the weed, because that’s where the sea urchin guys harvest.”

He reckons that because it’s all happening underwater, the powers that be don’t give a rat’s arse about the abalone industry.

“When the abalone virus was around, no-one cared. It was a bit different with horse flu — as soon as a horse got a cold, there was a person at every NSW/Victorian border crossing making sure an infected horse didn’t get in, because it affected everyone’s pockets through punting. There are a lot of things going on behind the scenes and we’re trying to get government funding.”

Grant Jr is also facing more personal challenges. “I try to stay out of the pub as much as possible,” he says. The Captain is, as always, sympathetic. “We hear you, mate. Wanna beer?” Nek minute, we’re at Lucy’s Noodles sipping Peronis and Coronas and chowing down on the best Chinese food that’s ever passed The Captain’s lips. And yes, abalone is on the menu.

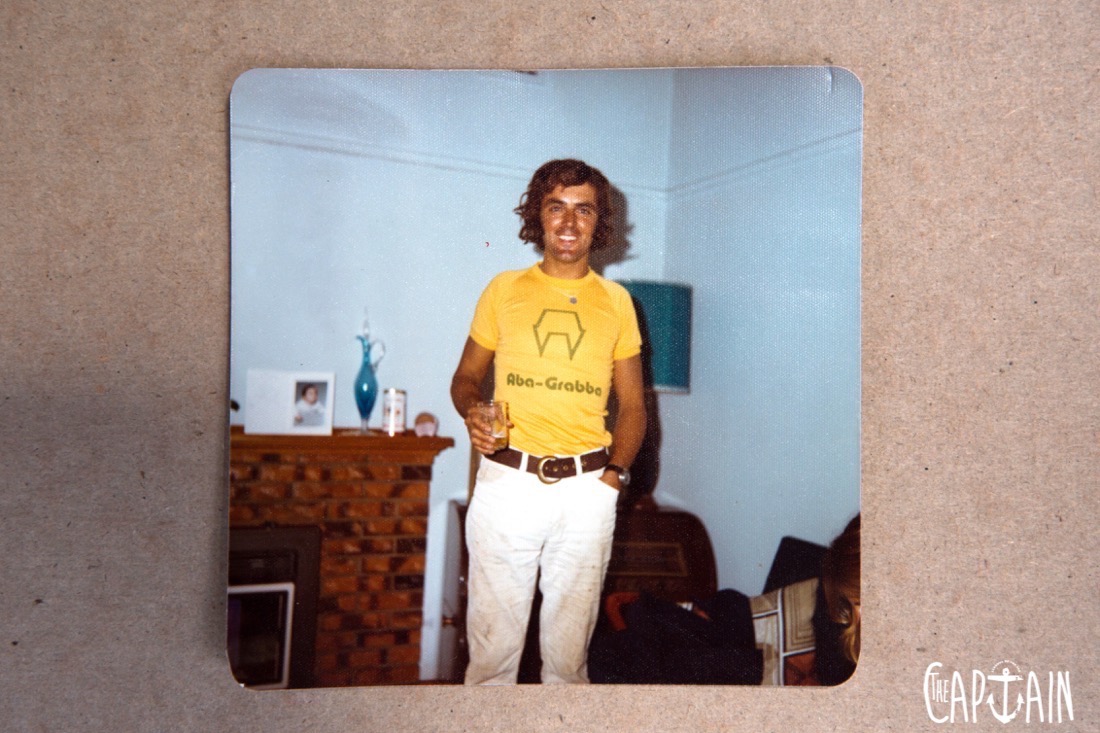

NO REST FOR ABBA-GRABBA

Visitors to Bastion Point are probably familiar with the green-and-gold Shark Cat 23 known as Abba-Grabba. It sits behind an old red Massey Ferguson tractor not far from the boat ramp. On calm days you can see it lumbering down to set crayfish pots. It’s the same ab-snatching, race-winning boat that was once owned by Grant Shorland Sr. (The green-and-gold colour scheme was his trademark livery, possibly inspired by Bruce Osborne’s BP service station that had served him so well.) This proud 23 is now in the capable hands of John “Blackie” Black. Blackie’s pretty handy on the abalone, too. He used to trade abs with his local restaurant for a feed before raising the bar to two shillings a pound. Then he hit his commercial straps in Mallacoota in the late ’60s, earning the big bucks. These days, Blackie hauls crayfish pots from the big twin-hull, continuing the fine tradition of Shark Cats in the Mallacoota region. You can read all about Blackie’s adventures, including his record spearfishing feats, in issue #11 of The Captain.

Recent Comments